On 12 April 2011, Advocate General Trstenjak delivered her Opinion in Case C-145/10, Painer v Standard VerlagsGmbH et al., in which the ECJ has been asked to give preliminary guidance on various questions concerning copyright in portrait photos used in news reports.

Because the contested photos and photo-fit were reproduced without her consent and without crediting her as the author, Painer brought an action against the newspaper publishers seeking a prohibitory injunction and payment of remuneration and damages.

By means of its reference for a preliminary ruling, the Austrian court (the Handelsgericht Wien) wants to ascertain, inter alia, whether the publication of the photo-fit is to be regarded as a reproduction of the photographic template used for its production and whether the publication of the portrait photos falls within the ambit of the exception or limitation to the reproduction right for quotations (Article 5(3)(d) of the Infosoc Directive) or for the purpose of public security (Article 5(3)(e) of the Infosoc Directive).

This blog post concentrates on the latter question concerning the scope of the applicable exceptions and limitations. In a subsequent blog post the copyright-related questions regarding photo-fits and the notion of originality in photographs will be dealt with.

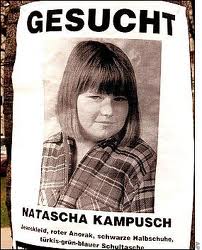

In respect of the application of the exception or limitation to the reproduction right for the purpose of public security (Article 5(3)(e) of the Infosoc Directive), the AG concludes that the relevant criterion is ‘whether the reproduction is objectively capable of pursuing purposes of public security’ (para. 153). She suggests that the referring court will have to examine what purposes were pursued by the original search appeal in connection with the abduction of Natascha Kampusch in 1998 and whether those purposes were fulfilled with her escape in 2006 and the suicide of her abductor immediately thereafter. She argues that a search appeal that has already been completed can no longer be assumed to objectively pursue a purpose of public security (para. 156).

Furthermore, the AG finds that, in this specific case, the referring court must also examine, in conformity with the three-step test, whether the legitimate interests of the right holders are not unreasonably prejudiced. According to the AG, the author’s interests may be unreasonably prejudiced ‘if the reproduction of the contested photos serves primarily to illustrate a report about Natascha K. and assistance with a search appeal on the part of the public security authorities takes on secondary importance to that purpose’ (para. 158). This sheds an interesting light on the AG’s opinion in the present case. Without stating so outright, she seems to imply that the use of the photos may perhaps have been not for the purpose of public security, but for the purpose of ‘sensationalizing’ the news reporting after Natascha’s escape from her abductor – something that certainly is not covered by the exception or limitation for the purpose of public security.

Presumably for the same reason the AG interprets parts of the exception or limitation for quotations fairly restrictively. She concludes ‘that the framework for consent-free quotations under Article 5(3)(d) of the directive is exceeded where the name of the author of a photo is not indicated, even though this did not turn out to be impossible. Indicating the author’s name does not turn out to be impossible where the person making the quotation has not taken all the measures to identify the author which appear reasonable having regard to the circumstances of the individual case’ (para. 207). In my opinion, this suggests a fairly far-reaching responsibility for persons quoting a work to ascertain the source and the author’s name. However, since the quotation right serves to realize freedom of opinion and freedom of the press, the AG assures that ‘the criterion of impossibility should not be subject to such high requirements that the quotation right no longer applies in practice if the author cannot be identified’ (para. 196).

Additionally, the AG emphasizes that a quotation must be for purposes such as criticism or review and that there must be a material reference back to the quoted work in the form of a description, commentary or analysis. In her view, the quotation must be a basis for discussion (para. 210). She adds: ‘In particular where the contested photos were merely intended to be used as a “teaser” to arouse the interest of readers without discussing those photos in the accompanying text, it cannot be assumed that there were quotation purposes within the meaning of Article 5(3)(d) of the directive’ (para. 211).

Although it needs to be seen what the ECJ eventually decides in this case, the latter statement reminds us that the exception or limitation for quotations does not always bring relief, for example, to bloggers that wish to make their posts more appealing by adding a photo or picture. While it seemingly allows me to quote the photo produced by Eva-Maria Painer in this blog post (provided of course that I indicate her as the author of the work), bloggers cannot rely on this exception or limitation where they use a photo merely for illustrative or humoristic purposes. Perhaps can they bring another copyright exception or limitation into play, such as the parody exception, but in the absence thereof, they may well be infringing someone’s copyright. To the extent that the usage can be considered harmless, therefore, an argument can perhaps be made for the introduction of a statutory open norm, such as a “fair use” type of defence advocated elsewhere on this blog, to permit such usage.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.