Decision Landgericht (District Court) Hamburg of November 18, 2016 (file no. 310 O 402/16)

Introduction

In GS Media vs. Sanoma, the CJEU recently ruled that linking to illegal content may be considered to be a “communication to the public” and can therefore constitute copyright infringement (C-160/15 of 8 September 2016). The District Court Hamburg has now been among the first German courts to take account of the CJEU’s decision. The Hamburg court has, in particular, interpreted what constitutes a “for profit” link and what duties the linker has to check the legality of the content linked to.

Background

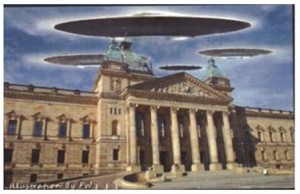

The claimant was the photographer of an architectural photo that showed only a building in the original version as can be seen below:

An adaption of this photograph was published on a website without the claimant’s consent. In the adapted version, flying objects that looked like UFOs were edited into the sky:

The defendant posted a link to the website, which made available the illegally adapted photo. This link was made available on the defendant’s website, which sold teaching material published by the defendant. In preliminary injunction proceedings, the applicant requested that the defendant be ordered to remove its link to the website that showed the adaptation of the photograph.

When the applicant became aware of the defendant’s link they sent a written warning to the defendant to refrain from further linking to the website on which the adaption of its photography was displayed. But after receiving the applicant’s written notice that the link went to an unlawful adaption, the defendant refused to take down the link on its website.

In fact, the defendant declared in writing that it did not believe that as a link setter it had a duty to investigate whether the adaption of the photograph was legal. Furthermore, the defendant even expressly said that it was aware of the recent CJEU judgment in GS Media vs. Sanoma. According to this decision no such duties would apply to link setters since the judgment of the CJEU would have been regarded as unconstitutional under German as well as European law.

The District Court decision

The District Court Hamburg allowed the applicant’s request and therefore restrained the defendant by way of a preliminary injunction from any further linking to the adapted photograph. According to the court, the defendant had to desist from such linking since the link infringed the right of the photographer to communicate to the public.

In that regard the District Court stated that the term “making works available to the public” within the meaning of § 19a German Copyright Act (“öffentliche Zugänglichmachung”, see here) shall be defined in light of Article 3 (1) Copyright Directive 2001/29. In this context, the court explicitly referred to the interpretation of Article 3 (1) Copyright Directive 2001/29 given by the CJEU in its recent decision GS Media vs. Sanoma (District Court para. 10).

In GS Media vs. Sanoma, the CJEU for the first time stated that linking to works freely available on another website without the consent of the right holder can be considered to be “communication to the public” (CJEU para. 43) within the meaning of Article 3 (1) Copyright Directive 2001/29. Hereinafter, the CJEU turned to the question of whether a communication to the public can only be assumed if the linker knew that the linked content was illegal. In this regard, the CJEU took the view that a differentiation must be made in order to determine what duties apply to linkers: Is the posting of the link carried out for profit or is the linker an individual who did not post the link for profit?

- If the posting of the link is carried out by a person who is not seeking to make a profit the court must take account of the fact that such a person may not know and cannot reasonably know that work had been published on the internet without the consent of the copyright holder (CJEU para. 47). But in contrast, when it is established that the person knew or ought to have known that the link provides access to a work illegally placed on the internet, a “communication to the public” can be assumed. This is particularly the case if such a person was notified thereof by the copyright holder (CJEU para. 49).

- When the posting of a link is carried out for profit, according to the CJEU, it can be expected that the person who posted such a link carries out the necessary checks to ensure that the work concerned is not illegally published. Therefore, it must be presumed that the posting has occurred with the full knowledge of the protected nature of that work and the possible lack of consent to publication on the internet by the copyright holder. According to the court, there is a rebuttable presumption that such a linker ought to have known (CJEU para. 51).

In summary, it can be concluded that, according to the CJEU, the standard of due care is stricter for profit-making linkers than it is for non-profit linkers as only the former have an obligation to carry out investigations regarding the legality of the linked content.

The District Court Hamburg based its ruling on these findings of the CJEU in GS Media vs. Sanoma and therefore held that by linking to the website with the photograph at issue, the defendant could have made it available to the public pursuant to § 19a German Copyright Act (District Court para. 37).

Firstly, the District Court checked that the copyright holder had not given its consent to make the (in this case: adaption of its) work available to the public (District Court para. 43). Such consent was ruled out, so the photo was available on the internet illegally.

Subsequently, the court had to look at the subjective criteria that determine whether linking to illegal content constitutes a communication to the public. Here, the Hamburg court had to differentiate between for profit and other linkers. Since the CJEU did not define which activities of a for-profit linker must in fact be for profit, the District Court Hamburg had to interpret the decision of the CJEU in this respect. The District Court held that the CJEU’s decision should, in this regard, not be understood in a strict sense (District Court para. 47). It could not be regarded as necessary that the setting of the link itself is profit-making, for example through generating a high number of clicks on the website. Rather, it needed to be seen as sufficient if the website itself made profit and, therefore, the linking by the defendant had to be regarded as “for profit” in the case at issue.

The defendant also could not rebut the assumption that he knew that the photograph was illegally published in the present case. This is due to the fact that the applicant had notified the defendant that the link went to an illegal adaption of the photo, but even after this notification the defendant refused to take down the link. Consequently, the court noted that the defendant acted with intent when he kept the link on its website (District Court para. 48).

Comment and outlook

The first interesting element in the ruling of the District Court is the opinion of the court concerning liability for linking to illegal content. In this regard, the court ruled on the question of the liability of link setters, which had been left open by the CJEU in GS Media vs. Sanoma. As discussed above, the District Court Hamburg was the first German court to interpret the CJEU’s decision concerning what constitutes the posting of a link “carried out for profit” (CJEU para. 51).

However, the decision of the District Court Hamburg also left some questions unanswered.

Regarding the liability for linking to illegal content in cases of for-profit linkers, the circumstances under which the linker ought to have known that the link went to illegal content are still not clearly defined. Neither the CJEU nor the District Court Hamburg clarified how far for-profit linkers must go in order to check that their links do not go to unlawful content. In this case, the District Court did not need to rule on this question since the linker was notified that the link led to an unlawful photo in the case at hand and therefore acted not with negligence but with intent.

In this context, a look at national concepts of negligence does not seem fruitful, as they lack harmonisation at EU level. Rather, the EU concept of prevention duties for intermediaries pursuant to Art. 8 (3) Copyright Directive could become the raw model (see for hosting provider CJEU C-324/09 – L’Oréal/Ebay paras. 128 et seq.; see for access providers CJEU C-314/12 – UPC TeleKabel/Constantin para. 37). This concept of prevention duties includes a flexible approach, balancing all affected interests.

When one takes a closer look, another open question that remains is: What obligations arise for linkers in terms of links in editorial contexts? The Bundesgerichtshof (“BGH”) as Germany’s highest civil court has already commented on this question in its decision AnyDVD. The court ruled that in the interest of the freedom of speech and the freedom of press, linking of an editorial internet service to the illegal offer can be allowed, if the editorial content discusses the legality of such offers without making such content its own content (BGH para. 26). With the Sanoma concept of the CJEU, a thorough balancing of interests would need to be applied. And it cannot be ruled out that under the Sanoma concept, the result would be the same.

Besides, many other questions regarding the term “communication to the public” have not yet been answered. In this context, in particular the decisions of the CJEU in the cases Filmspeler and Brein/Ziggo still remain interesting.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.