The European Union is working on a dramatic change to the regime that governs the liability of online intermediaries established with the E-Commerce Directive (Directive 2000/31/EC). Art. 14 offered a safe harbour for hosting service providers who do not have actual knowledge of infringing content and who, on obtaining such knowledge, act “expeditiously to remove or to disable access to the information”. Art. 15 ensured that there was no general obligation to monitor.

Art. 13 of the Proposed Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (COM(2016) 593 final) attempts to replace the requirement to act upon obtaining constructive knowledge with an obligation to filter infringing content before it is hosted. There are various drafts of Art. 13 in play, including a position adopted by the Council of the European Union on 25 May. The JURI Committee will vote on its own amendments on 20 June. A summary of the progress of Art. 13 is available here.

Art. 13 is lauded by rightsholders, in particular from the music industry, as a solution to bargaining troubles vis-à-vis internet giants, such as Google (owner of YouTube) and Facebook. Digital innovators and civil liberties groups see Art. 13 as an attack on foundational principles of the Internet (#SaveYourInternet; https://saveyourinternet.eu/).

Given the virulence of debate, and the huge economic and cultural impacts of the regulatory approach adopted, it is surprising how little we know about the functioning of the regime as it currently operates. After nearly two decades of “notice-and-takedown” we should be able to rely on a body of empirical research for policy making.

Studying Takedown

One thing we do know is that the volume of takedown requests has increased massively over time for certain Internet service providers. This increase has been facilitated, on one side, by computers (responsible for sending so called robo-notices), while on the other side computers have been proposed as a solution for dealing with massive numbers of rightsholder requests (algorithmic filtering).

When the content to be removed is an unambiguous piratical copy, automated systems make sense (as long as the takedown request is accurate and valid, a separate problem discussed by Karaganis, Urban and colleagues). The problem becomes more complex when human judgment is needed to assess the validity of a takedown request, for example in the case of content that might benefit from a statutory copyright exception.

Using data collected from user-generated music parodies on YouTube, we studied the pattern of takedowns over a five-year period. We did this because there was very little known about why rightsholders act to request removal of content. We also wanted to know if rightsholders were actually as sensitive as they claimed over a proposed exception for purposes of parody, introduced in the UK in 2014. Our data consisted of 1,834 parody videos, based on 343 commercially successful pop songs that charted in the UK for at least 1 month in 2011. This technique allowed us to study features of the original music track as well as its parody off-shoots, to see whether any had a significant effect.

How much content was removed?

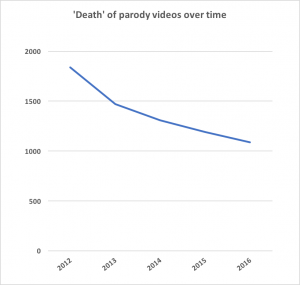

One headline result is that from our sample of 1,834 user-generated parody videos, some 32.9% were removed for copyright reasons between January 2012 (when they were first observed) and December 2016 (the end of the study period). This statistic on its own is illuminating, since YouTube has a policy not to disclose takedown rates (presumably because this might invite scrutiny from rightsholders and regulators). Another observation is that the rate of takedown is not as skewed as one might expect. Rather than a quick and intense culling of videos at the start of the observation period, we find a relatively gradual and continuous rate of removal, with takedowns occurring long after the original pop songs have slipped from the sales charts and radio airwaves. It is highly likely that takedowns of our original cohort of videos from 2012 are still occurring today.

One headline result is that from our sample of 1,834 user-generated parody videos, some 32.9% were removed for copyright reasons between January 2012 (when they were first observed) and December 2016 (the end of the study period). This statistic on its own is illuminating, since YouTube has a policy not to disclose takedown rates (presumably because this might invite scrutiny from rightsholders and regulators). Another observation is that the rate of takedown is not as skewed as one might expect. Rather than a quick and intense culling of videos at the start of the observation period, we find a relatively gradual and continuous rate of removal, with takedowns occurring long after the original pop songs have slipped from the sales charts and radio airwaves. It is highly likely that takedowns of our original cohort of videos from 2012 are still occurring today.

Of the 343 commercial songs that formed the seed of our sample, it was rare for a single track to have all of its parodies removed. We could describe such a pattern as the “Prince effect”: e.g. when a single artist or label objects so strenuously to online uses that all exemplars are removed. Instead, rightsholders in our study appeared to pick and choose from among detected parodies, leaving some up while removing others.

What kind of content was removed?

In responding to consultations leading up to the introduction of a parody exception in the UK, some rightsholders were adamantly opposed to this reform. Among their claims were that 1) popular parodies might substitute for their originals, 2) parodies could threaten the moral and artistic integrity of artists’ work, and 3) rightsholders would lose a licensing revenue stream represented by would-be commercial users.

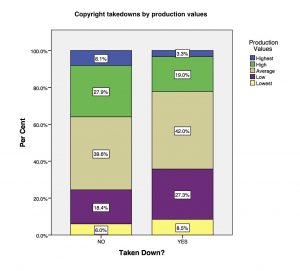

In terms of commercial substitution, we found no evidence that rightsholders were concerned. In fact, the more views a parody received and the more commercial its production values, the less likely it was to be removed.

In terms of commercial substitution, we found no evidence that rightsholders were concerned. In fact, the more views a parody received and the more commercial its production values, the less likely it was to be removed.

Among those parodies that criticised the original in the most derogatory manner, there was no statistically significant increase in takedown. In fact, weapon and target parodies, which either take aim at the original artist or use the original as a weapon to make a political statement, enjoyed lower rates of takedown compared to parodies where there was no discernible critical point. This reinforced the finding that the quality and sophistication of the user-generated content most directly influenced its susceptibility to takedown.

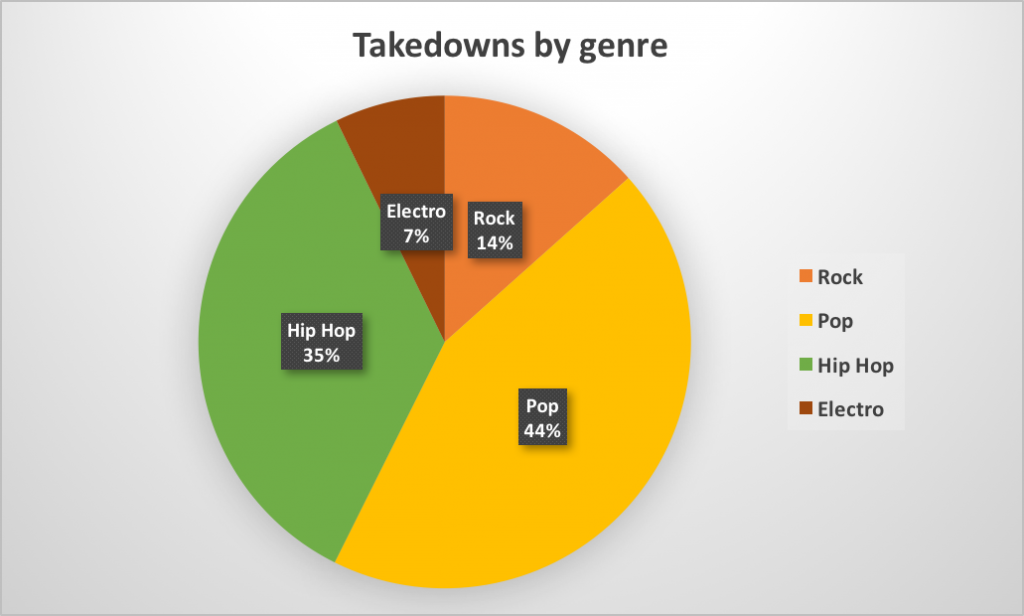

We also found something puzzling when looking at the culture of commercial music production. Whether a song originated from a major or independent label had no effect on takedowns, but the genre of music did. Popular and Hip hop music genres were associated with higher rates of takedown, while rock music parodies were the least likely to be removed.

Publishers of musicians from the USA were significantly more tolerant of parodic uses than their European counterparts (including the UK), suggesting an effect linked to Fair Use.

Why does this matter?

For an amateur-quality parody of a popular hip hop music track, the odds of removal were higher than for, say, a professional-looking parody of a rock song from the same year. We don’t know exactly what explains this statistically significant effect. Hip hop traditionally tolerated sampling as part of its art form, but commercial publishers of hip hop music today appear less tolerant of parodic uses.

The conclusion – like with most empirical research – is that we need to know more. Since the pattern of takedown seems to follow an arbitrary pattern that rewards certain skill levels and music genres, the potential impact on diversity and freedom of expression is concerning.

Under these circumstances, the right regulatory response is caution. The obligation to act upon constructive knowledge (established under the e-Commerce Directive) should not be replaced by a filtering obligation. If current powers under a notice-and-takedown regime already seem to have deeply problematic effects, policy makers should not grant further powers lightly.

The authors’ study: Kristofer Erickson and Martin Kretschmer, “This Video is Unavailable”: Analyzing Copyright Takedown of User-Generated Content on YouTube, 9 (2018) JIPITEC 75 is available here.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.