Like most copyright systems, French copyright law does not leave much room for the freedom of authors of transformative graphic works (also called “derivative works”).

Three interesting cases on derivative works, two involving Jeff Koons and one Tintin, have recently put French copyright law in the international spotlight (e.g. here and here). The American transformative artist Jeff Koons was condemned by the Court of Appeal of Paris for copyright infringement in 2019 and in 2021 for sculptures from the ‘Banality’ series (see hereunder), whereas the Court of First Instance of Rennes, in a judgment of 10 May 2021, ruled that the author of paintings incorporating the Tintin character in flirtatious situations could rely on the exception for parody.

Derivative works under French copyright law

Article L.113-2 paragraph 2 of the French Intellectual Property Code (“IPC”) defines a ‘composite work’ as ‘a new work in which a pre-existing work is incorporated without the collaboration of the author of the latter work’. A composite work is therefore a derivative work, i.e. simple incorporations (e.g. music synchronised in an advertisement) and adaptations (e.g. a remake or an adaptation of a book into a film).

Article L.113-4 IPC states that ‘A composite work shall be the property of the author who has produced it, subject to the rights of the author of the pre-existing work.’ In addition, Article L.122-4 IPC provides that the ‘translation, adaptation or transformation, arrangement or reproduction by any technique or process whatsoever’ of a work is unlawful.

Therefore, unless the author of the transformative work can rely on a copyright exception (such as parody) or limitation (such as freedom of expression), he/she will have to enter into an agreement with the author and/or owner of the first work.

The facts in the Koons and Tintin cases

Jeff Koons has been condemned three times in cases relating to his very successful ‘Banality’ series of sculptures, which he presented in 1988: once in the US and twice in France, each time using the parody defence without success.

Out of interest, I will start by briefly mentioning (without studying the case) the first copyright infringement case Jeff Koons lost, which was brought before a U.S. court about 20 years ago by Art Rogers, a professional photographer. Koons had made a sculpture from one of Rogers’ ‘Puppies’ photographs, as presented hereunder. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit rejected Jeff Koons’ fair use argument (section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976) based on parody (Rogers v. Koons, 960 F.2d 301, 2d Cir. 1992).

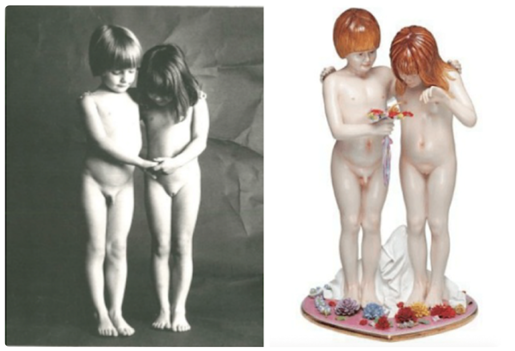

In a judgment of 17 December 2019, the Court of Appeal of Paris condemned Koons’ U.S. company, Jeff Koons , and the Centre Pompidou Museum for the same type of transformation of a photograph by Jean-François Bauret entitled ‘Enfants’ (children) taken in 1970, also for the Banality series. Koons called the sculpture ‘Naked’. The damages awarded in this case amounted to €24,000. The Centre Pompidou Museum presented ‘Naked’ in 2014 in the framework of a retrospective exhibition of the work of Jeff Koons in Paris.

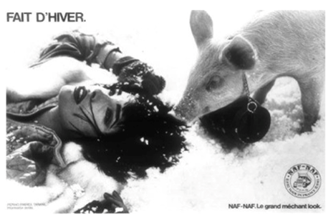

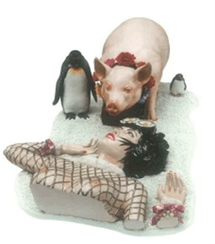

Finally, in a judgment of 23 February 2021, the Court of Appeal of Paris condemned Jeff Koons, together with Jeff Koons LLC, the Centre Pompidou Museum, the Prada Foundation and the French publishing company Flammarion, for copyright infringement. The damages awarded in this case amounted to over €200,000. This is another sculpture from the Banality series: Koons used a photograph for an advert created for the French prêt-à-porter (ready to wear) brand Naf-Naf in 1988, that had been published in various women’s magazines such as “Elle” and “Marie Claire”. The photograph features a young brunette woman with short hair, lying in the snow, a little pig leaning over her with a Saint Bernard rescue dog barrel around its neck. This visual was entitled “Fait d’hiver” (which literally means a winter event and is a pun on ‘fait divers’ which means a miscellaneous news item). The sculpture was presented in 2014 by the Centre Pompidou in the retrospective exhibition mentioned above.

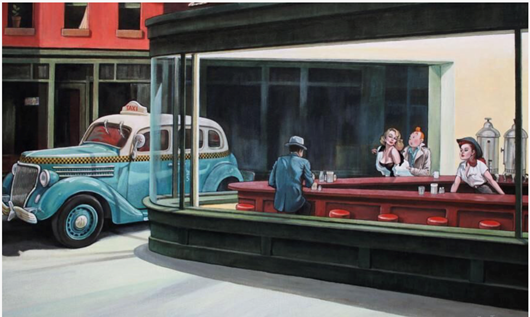

As for the facts of the Tintin case, in 2014 the French artist Xavier Marabout started making public works based on the Tintin character in flirtatious situations inspired by the paintings of the American artist Edward Hopper, such as in this work:

Those who know the Tintin comic book series (who doesn’t?) know that Tintin often gets involved in dangerous situations, but never in dangerous amorous or erotic situations. Moulinsart, the Belgian company that holds the rights to Tintin, and the heir of the author, Hergé, holder of the moral rights, brought a copyright infringement case against Marabout. Unlike in the Koons cases, the court found that Marabout could rely on the exception for parody.

The parody defence

In its 2014 Deckmyn judgment, the ECJ clarified the “autonomous concept of parody under art.5(3)(k) of Directive 2001/29/EC“ (discussed here); the essential characteristics of parody are the following:

- A parody must evoke an existing work. As we will see hereafter, in the Koons and Tintin cases, the courts tend to consider that this means that the public must be able to easily identify the parodied work, and that the parodied work must therefore be quite well known; this interpretation of Deckmyn is questionable ().

- A parody must be different from the parodied work (there must be no risk of confusion).

- A parody must constitute an expression of humour or mockery, but the ECJ also specified that “parody is an appropriate way to express an opinion” (Deckmyn Case, para. 25).

- The application of the exception for parody must strike a fair balance between, on the one hand, the interests and rights of the rightholders, and, on the other, the freedom of expression of the user of a protected work.

In France, Article L.122-5, 4° IPC provides that the rightholders may not prohibit parody, pastiche and caricature which comply with “the rules of the genre”. In light of the Deckmyn case, the French Supreme Court, in a judgment of 22 May 2019, adapted the traditional characteristics of the exception for parody under French copyright law (here).

In the Koons and Tintin cases, the courts applied the criteria set out in Deckmyn:

In its judgment of 17 December 2019, the Court of Appeal of Paris, referring to Deckmyn, dismissed the parody defence stating that the parody must allow the identification of the first work, which was not the case because the photograph ‘Enfants’ used by Koons to create the sculpture ‘Naked’ was not known. The Court of Appeal also based its finding on the lack of humorous intent.

In its judgment of 23 February 2021, the Court of Appeal of Paris ruled that the second work does not evoke the first work. In the absence of any reference or commentary in galleries or museums to the preexisting work ‘Fait d’hiver’, Koons does not establish that his intention was to evoke that work. The Court explains that the photograph ‘Fait d’hiver’, produced for the autumn-winter 1985 advertising campaign of the company Naf-Naf, was undoubtedly forgotten or unknown to the public at the time of the Jeff Koons exhibition at the Centre Pompidou at the end of 2014, so the public could not, on seeing the sculpture exhibited in the museum or reproduced in books or on the website www.jeffkoons.com, refer to the photograph published almost 30 years earlier for the purposes of an advertising campaign which lasted only a few months. The Court adds that since Koons did not present to the public any element that might suggest that his work is linked in a parodic form to the disputed photograph, the public was unable to detect the evocation of the pre-existing photograph in the disputed sculpture and perceive its parodic dimension. The Court therefore rejected the parody defence.

The ‘Fait d’hiver’ judgment seems to consider that the parodied work must be easily identifiable by the public over 30 years after the second work was created, which is questionable (see above). But in any event, there is no humorous intention (the parody is funny only because the rescue pig of the parodied work was funny in the first place, without any additional humour, mockery or opinion from Koons).

In its judgment of 10 May 2021, the Court of First Instance of Rennes ruled that the author of the works parodying the Tintin character could rely on the exception for parody. The Court found that all the conditions for the existence of a parody were met:

- The parodied work is easy to recognise, because the characters of the albums are easily identified by the public.

- The parody is different from the parodied work, and there is no risk of confusion, since the author of the parody chose a medium (acrylic painting) different from the comic strip medium, with a composition that also evokes the work of Hopper, quite different from that of Tintin, with the characters of the pastiche in situations that are very different from Tintin’s environment.

- The humorous intention has been recognised by many people who have seen the works, as well as by journalists in newspaper reviews, such as: ‘La Provence’ of May 2017: “we loved the talented humour of Xavier Marabout’s Tintins, who merges the universe of Hergé with that of Hopper – ‘Les cahiers de la BD’ of 8 July 2019: “By putting Tintin into the settings of the American painter Edward Hopper, Marabout puts his finger where it makes us laugh: our little reporter is incapable of love… It’s offbeat, it’s fresh as paint and it’s not sad”.

- Finally, the Court studied whether the parody strikes a fair balance of interests, by analysing the economic situation almost like a US court would do under section 107 of the US 1976 Copyright Act. After calculating the economic issues in a “rough and approximative” way, as the Court admits, it finds that the parodist makes about €115,000 per year with his works (therefore less than €40,000 of actual income per year), which is rather modest in comparison with the sums Moulinsart makes with Tintin merchandising. One can wonder whether this type of calculation is the correct method to analyse the balance of interests; what happens if Marabout’s works start selling for millions of Euros? The Court however added that those who buy paintings in galleries are not the same as those who buy comic books and merchandising products (it would have been more accurate to say that the first products do not replace the second).

The rightholders lodged an appeal against this judgment. It is not possible to speculate on the outcome of the appeal, but we will note that Koons’ works are adaptations of photographs, turned into sculptures, with only minor changes, whereas Marabout plays with the Tintin character, deliberately and explicitly putting him in situations that are in contrast with Tintin’s personality traits and environment.

The freedom of expression defence

In the aftermath of cases of the European Court of Human Rights where copyright and freedom of expression had been opposed (here; in particular Donald Ashby and Pirate Bay), a judgment of 15 May 2015 of the French Supreme Court quashed a judgment of the Court of Appeal of Paris for breaching Article 10-2 of the European Convention on Human Rights (“ECHR”), causing a stir in France (here). In this case, a photographer, who had discovered that three of his photographs had been incorporated in several paintings without his permission, sued the painter of these derivative works for infringement of copyright. The Supreme Court held that before condemning the alleged infringer for copyright infringement, the Court of Appeal should have explained in concrete terms, as was requested by the alleged infringer, how a fair balance between the freedom of expression of the alleged infringer and the rights granted under copyright law could result in condemnation.

Since the 2015 judgment, the freedom of expression defence has been used in many copyright cases. However, in its judgment, the Supreme Court had deferred the case to the Court of Appeal of Versailles which re-judged the case on its factual and legal points. The Court of Appeal, in a judgment of 16 March 2018 (No 15/06029) dismissed once again the defence, ruling that the author of the second work did not establish how a fair balance between the protection of his freedom of expression and the protection of the photographer’s right required him to use those photographs. Moreover, the Court pointed out that the author of the second work had admitted that the photographs were substitutable and that he could just as easily have used other advertising photographs of the same kind.

This freedom of expression defence was used in the Koons cases, in addition to the parody defence. The Court of Appeal of Paris dismissed the defence in both cases:

In its judgment of 2019 (‘Naked’), the Court found that it is not established that the unauthorised use of the photograph was necessary for Koons to exercise his freedom of artistic expression. The Court explained that Koons, who could have used another work, did not try to obtain the authorisation of the author, whose identity he could not ignore (‘Enfants’ had been published and presented in exhibitions). Moreover, Koons could have expressed the same ideas and messages with another presentation of children.

In its judgment of 2021 (‘Fait d’hiver’), the Court explained that the photograph was not known to the public, who could not perceive the claimed transformative approach. The Court underlined that nothing justifies the fact that Koons, who himself holds a very prominent position on the art market, refrained from seeking out the author of the photograph from which he intended to draw inspiration, to obtain his authorisation. The Court therefore ruled that the implementation of copyright protection for the photograph “Fait d’hiver” constitutes a proportionate and necessary limitation on Jeff Koons’ freedom of creative expression.

These two judgments are now final, as they have not been appealed before the Supreme Court. Unfortunately, we will therefore have to wait a long time before the French Supreme Court gives its position on the criteria to be used by the lower courts in the balancing exercise between the rights of the authors of the first works and the rights of the transformative artists.

It is however interesting to note that Koons’ works exist and will continue to exist: the court ordered Koons to stop the infringement acts on the French territory (showing the counterfeiting works on his website, presenting the works in museums…), but the works are still accessible from France on the internet on other websites and the plaintiffs did not – could not – ask for the sculptures to be destroyed. In the ‘Fait d’hiver’ case, the plaintiff asked for the sculpture to be confiscated and given to the French State; this claim was dismissed by both the Court of First Instance and the Court of Appeal who considered that the measure would be disproportionate since the infringement acts have been going on for so long, and because the composite work is that of a foreign artist. In terms of copyright law, one could question the logic of these arguments of the court, but it is certain that transformative works are not mere counterfeiting products and cannot be treated as such… Where transformative works are concerned copyright law faces a ‘fait accompli’ situation, which leaves everyone unsatisfied.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.

Great insights into the complexities of derivative works in French copyright law. The case study of Koons and Tintin is fascinating!