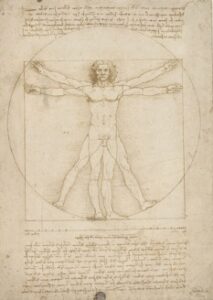

In late 2022, the Court of Venice issued an interesting order restraining the use of the image of a well-known piece of Renaissance art by Leonardo da Vinci: the Study of the Proportions of the Human Body in the Manner of Vitruvius, also known as the Vitruvian Man.[1] The artwork is held by the Italian state museum Gallerie dell’Accademia of Venice, which, along with the Italian Ministry of Culture, initiated the precautionary proceeding against the German company Ravensburger and its Italian subsidiary for producing and selling the puzzle and reproducing the work’s image. Once made public, the judgement immediately attracted quite a significant amount of attention, mainly for its unbending application of the Italian code of cultural heritage and landscape, its ambitious aim to stretch the application of the personality rights of name and image, and the peculiar, although not explicitly stated, link with copyright law.

Dated c. 1490, the drawing is one of Leonardo’s most iconic and replicated works, representing his conception of the archetypal proportions of the human figure theorised by the ancient Rome architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio in his De architectura (c. 15 B.C.). The masterpiece is equally understood as an exemplary representation of the ideal equilibrium between the rational and emotional spheres of life. For the unique symbolism of its balancing scope, the image was also chosen to feature on Euro coins. Nonetheless, this case is anything but balanced.

On appeal from an earlier order, the present ruling affirmed the Court of Venice’s competence to rule on the infringing conduct, i.e., the use of the work’s image to produce and distribute puzzles faithfully reproducing it by all the companies of the Ravensburger group. The Court applies Italian law cross-border to the unitary set of conducts, based on an economic-functional link among all company divisions, indicating as the main criterion of connection with Italian jurisdiction the forum damni ex Article 20 of the Italian code of civil procedure (c.p.c.), resulting in the place where the cultural heritage institution having the cultural good in consignment and suffering the damage is found.

Setting aside the private international law aspects, the case deserves examination on two main grounds. First, the claimants demand the application of articles 6, 7, and 10 of the Italian Civil Code (c.c.), which refer to a person’s rights to name and image. Second, they argued for infringement of Italian cultural heritage norms as Ravensburger failed to obtain permission from the museum to use the image of the Vitruvian Man for commercial purposes.

Opposing the claimants’ arguments, Ravensburger challenged the cross-border application of Italian law, alleging that the claims conflict with article 14 of Copyright Directive in the Digital Single Market (CDSM) Directive since they attempt to unlawfully impose property assertions on public domain works. Ravensburger also denied the valid application of Articles 6, 7, and 10 c.c. as unjustified given that no debasement or watering of the image had occurred.

In the precautionary proceeding, the Court acknowledged the merits of prima facie evidence (fumus boni iuris) and the urgency (periculum in mora), further stating that the infringing conduct caused severe and irreparable harm to the claimants.

In the Court’s view, non-pecuniary damage would be caused primarily by the debasement of the image and denomination of the cultural good, due to prolonged and unsupervised use of the work’s reproduction for merchandising. The Court does not address the issue of resorting to the rights of personality with the necessary concern and simply allows it on the grounds that the Galleries are the custodians of the work and only they can assess the compatibility of the use of name and image with the cultural destination of the work.

Second, the Court established the violation of Articles 107-109 C.b.c. In combination, these provisions give cultural heritage institutions the option to request, where applicable, concession fees and a percentage of royalties, provided that they oversee the compatibility of the conceded use with the cultural destination of the work.

As a result, the Court of Venice prohibited Ravensburger from further using the image of the Vitruvian Man for commercial purposes, in any manner or through any medium. It also ordered the company to pay 1.500 euros for each day of delay in the execution of the judicial order, as well as the publication of the decision on a large scale.

As it is evident, the image of the Vitruvian man is in the public domain and it has never been subject to copyright. From this perspective, anyone should be able to access and use it freely for any purpose without encountering any additional entitlement to exclusive rights. One question that arises in this scenario is whether Article 14 CDSM Directive applies in this case. Two arguments can be advanced for this interpretation.

First, the rationale behind Article 14 CDSM Directive is clear. It aims to ensure that no copyright protection applies to the reproduction of works of visual art in the public domain unless they meet the threshold for originality. This implies not only that merely reproducing a public domain work does not attract copyright protection but also that they can be freely used without further restriction. This is confirmed by a close reading of Recital 53 CDSM Directive.

Second, there is a relatively clear understanding that the two dimensions—copyright on the one hand and cultural heritage law on the other—may eventually intersect. This is confirmed by the fact that Italian policymakers felt the urge to provide an explicit derogation for C.b.c. provisions when drafting the domestic transposition of the EU provision, namely Article 32 of the Italian Copyright Act (l. 633/1941, l. aut.). The fact that the Italian legislature, in its transposition, did not explicitly affirm a new right of reproduction does not change the outcome that works in the public domain may be subject to a different regime which, to quote the Court of Venice, establishes their “exclusive rights of exploitation”.

The risk was anticipated by many voices across Europe, including Communia, but also during the Italian parliamentary proceedings. These concerns were expressed in stakeholders’ position statements, including the joint appeal for the free reuse of cultural heritage images in the public domain led by Creative Commons, and echoed in the Italian scholarly analysis shortly after enacting the new rules on the digitisation of cultural heritage. These calls were not successful in preventing the risk but merely in predicting what could come next: a “minefield” for the public domain, as eloquently put by Cristiana Sappa.

This has already emerged in previous and not-so-old cases on the copyright/cultural heritage intersection, even though from relatively different perspectives. One of the most recent examples is the dispute (not yet decided) around the use of the images of the Birth of Venus by Michelangelo in fashion design; the others are the controversy over the use in the advertising of the image of the Teatro Massimo in Palermo[2] and the multiple claims against the use in the marketing of David by Donatello.[3]

Concerns about the lack of coordination among copyright, cultural heritage, and data regulations were explicatively addressed by ReCreating Europe’s policy recommendations for the digital future of cultural heritage, according to which, should other cases be brought before the national courts – and in the absence or even unwillingness of a short-term normative intervention of EU legislature –the ultimate possibility is for the judiciary to interpret national norms in compliance with EU law.

Although this may ultimately call for the intervention of the Court of Justice of the EU, Italian courts may still achieve a more balanced approach on a constitutional-oriented reading of the applicable statutory norms oriented to safeguard and enhance access to, enjoyment of, and use of cultural heritage. In this effort, they should first look to Article 9 of the Italian Constitution, which promotes cultural development and research while safeguarding the nation’s natural and cultural heritage. This provision applies to the instant case in two ways. First, the valorization of cultural heritage can be reached by promoting the use of the work’s image. Second, the reproduction of a work’s image on a puzzle does not seem to reasonably put in danger the good itself or its cultural value and destination.

In short, the original aim of Article 14 CDSM Directive—upholding the public domain and supporting the circulation of works, including the reproduction of their images—risks being seriously undermined. Any restriction on the freedom to use visual arts works in the public domain, also in terms of strong proprietary claims, as Giorgio Resta warns, or of pseudo-copyright on cultural heritage, indisputably affects the right to culture as a right to access and participate in cultural life by anyone. As such, the pretext to valorize the cultural good by imposing a different exclusive regime is neither based on solid grounds nor genuinely supported by empirical studies that unambiguously show that exclusivity fosters innovation in the cultural domain. On top of that, as the case demonstrates, the public domain may receive other threats from an aggressive extension of the scope of personality rights.

As an additional remark, this is particularly true in a situation like the one under consideration, where the work is significant for humanity at large. Yet, its use is already drastically limited by the paucity of its display, justified by preservation reasons to avoid deterioration of the tangible, only increasing the scarcity of its availability. Furthermore, in the case in question, the work is a puzzle that, by its nature, is an informative game that may reasonably serve educational purposes and contribute to the valorization of the cultural good itself.

The Vitruvian Man was the protagonist of another legal controversy that, in 2019, when its loan to the Louvre was questioned based on its fragile nature and iconic significance.[4] On that occasion, the country’s aspiration to maximise the potentiality of cultural heritage by allowing the world to see the artwork prevailed.

The tone of the judicial order under discussion is solemn. The court accounts for irreparable damage on the sole fact that Ravensburger made an arbitrary and unsupervised reproduction that did not allow the museum to assess the appropriateness of using the image with the cultural value of the work. In reaching this conclusion, it stressed the importance and value of cultural heritage for society, but it confined it to local and national boundaries. This conflicts with the idea that cultural heritage has a universal calling. From a different angle, allowing others to use the image commercially would not affect or impede the merchandising capacity of the custodian cultural heritage institution. Besides, it seems that, if the commercial use had been authorised, the debasement of the image would have been excluded. Finally, it is also worth clarifying, sharing the views of De Angelis and Vezina, that Italian law does not mandate cultural heritage institutions to charge fees for commercial use of the work’s image. This leaves an ample margin of discretion that may allow a flexible and balanced approach.

Finally, the Court of Venice’s decision is problematic in that it employs the dangerous metaphor of embezzlement (or misappropriation) to qualify the infringing conduct and strengthen the idea that rigid protection is needed to support the actual value and immaterial significance of the cultural good. Consequently, future controversies are likely to follow. This is a context where, as the same court admits, these issues are new and lack a close judicial direction. Either way, in this unclear and mystifying scenario, we are pretty far from a fair balancing of competing interests that does justice to the ideal proportionate equilibrium of Leonardo’s vision.

In conclusion, it is worrisome to witness a drift towards a structured and unbalanced approach by national courts that, despite applying norms belonging to a different domain, affects the compromised and hard-fought solution that EU policymakers have reached in copyright law. From this perspective, the contemporary interpretation of the Vitruvian Man by Mario Ceroli in his three-dimensional signature work Squilibrio (1967), literally Imbalance, provides a more accurate depiction of the current reality.

[1] Tribunale di Venezia (sitting en banc), decided on October 24, 2022, and published on November 23, 2022.

[2] Tribunale di Palermo, decided on September 15, 2017 and published on September 21, 2017.

[3] Tribunale di Firenze, decided on October 25–26, 2017; Tribunale di Firenze, decided on April 11, 2022.

[4] Tribunale Amministrativo Regionale (T.A.R.) Veneto, decided and published on October 16, 2019.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.

Do you think that the outcome of the tiral would have been different if Ravensburger would not have an office based in Italy?