Tackling the blurred lines between counterfeiting and ingenuity in the art world is certainly not an easy endeavor. Indeed, in a world where “nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed“, it is a rather daunting exercise for any court to draw the line between inspiration and imitation in copyrighted works, let alone in copyrighted art works.

In January 2024, in an attempt to tackle this hot topic, the Cairo Economic Court handed renowned Egyptian graphic designer, Ghada Wali, a six-month imprisonment sentence and a hefty fine over charges of plagiarizing artwork from Russian artist Georgy Kurasov (case no 69/2024); a controversial ruling that has sent ripples through the Egyptian creative community (See here, here, here, here).

Background

Wali’s predicament started on July 2, 2022, when Kurasov wrote on his personal Facebook page: “My paintings were used in Cairo subway without my permission and even mentioning my name! […] I am waiting for an official response about the theft of my paintings in a metro station” (See here, here). In fact, these allegations concerned four of Kurasov’s paintings that were displayed on the murals of Koliet El-Banat (Girls’ college) Cairo Metro station.

Luckily for the Russian artist, his accusations quickly caught the attention of RATP DEVM Mobility Cairo, a French subsidiary responsible for the operation of Cairo’s third Metro line. The former had contracted with Wali’s studio to redesign the station murals as part of an initiative to promote Egyptian civilization, heritage and culture. The French subsidiary stressed that a clause was indeed inserted into their agreement stating that the studio is responsible for providing original artistic designs, and that in the case of quoting or copying, it must obtain official legal approval from the original artists (See here). However, following Kurasov’s blunt accusations, and in less than a week, the Egyptian authorities and the French subsidiary responded by ordering the immediate removal of the murals and issuing an official apology to the Russian artist emphasizing their full respect for the intellectual property rights of everyone in Egypt and abroad (See here).

Nevertheless, despite the swift response from the relevant authorities, Kurasov decided to sue Wali before the Egyptian courts seeking to ascertain his copyright over his original works.

Cairo Economic Court’s Ruling

For the uninitiated, the Egyptian Copyright framework is set under book three of law no 82 of 2002 for the Protection of Intellectual Property Rights (Egyptian Copyright Law – ECL) where enforcement is protected through two distinct means, being civil and criminal proceedings. Nonetheless, it should be noted that enforcement of copyright under Egyptian law is often done through both claims in parallel and that infringement is primarily addressed through criminal sanctions (See here).

According to article 181 of the ECL, “without prejudice to any more severe sanction under any other law, shall be punishable by imprisonment for a period of not less than one month and by a fine of not less than 5,000 pounds and not more than 10,000 pounds, or any of those sanctions, any person who commits any of the following acts: […] (2) knowingly imitating, selling, offering for sale, circulation or rental, a work”, and “sanctions shall be multiplied according to the number of infringed works”.

The Cairo Economic Court, which possesses exclusive jurisdiction in all copyright-related matters was perfectly positioned, in this high-profile case, to unravel the intricacies of copyright infringement in the realm of art works under Egyptian law.

The case involved several investigations by the Egyptian prosecutor’s office which set up an expert committee from several public officials, notably from the Egyptian Ministry of Culture, to further investigate the accusations. The prosecutor’s enquiries proved several interesting points, namely that two of Kurasov’s paintings were published on his Facebook page on October 8, 2012 and thus are prior art work to Wali’s drawings; that all four works of Kurasov were deposited with the Russian Ministry of Culture between 1995 and 2012 as proved by the official certificates presented by Kurasov’s counsel; and, finally, that the authenticity of such certificates were confirmed by the Russian prosecutor’s office investigations.

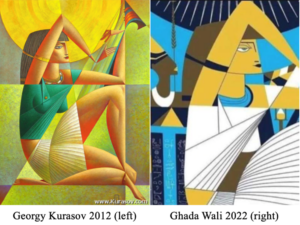

Moreover, the expert committee confirmed that Kurasov’s paintings are original works of his creation and that Wali’s drawings replicated Kurasov’s drawings. The court explains that, according to an expert report from the Egyptian Ministry of Culture’s art restoration department, Wali’s drawings lacked any originality or ingenuity and, given the similarities between both works, amount to plagiarism.

Wali, who categorically denied any plagiarism allegations in the media, stressed vehemently that she was predominantly inspired by ancient Egyptian art, and implemented the shapes using the cubist technique put forward by the infamous Picasso. Moreover, she attributed any similarities in her designs to mere commonalities in artistic styles and affirmed that resemblances can inadvertently occur in creative works. Defense counsel corroborated these arguments with detailed and technical explanations presented to the court. The latter was also asked to mandate a new expert committee and to order the invalidation of the initial expert report as the initial experts were not subject to any cross-examination during the proceedings and lacked the relevant expertise. According to Wali’s defense counsel, the mandated expert should have been an Egyptologist and not an art restoration expert since she argues that her works were inspired by ancient Egyptian murals and not Kurasov’s paintings.

In spite of the counter-arguments presented, the court completely avoided this debate and concluded in a very bold statement that none of Wali’s arguments should be replied to in the verdict. Instead, the court opted to render its judgment solely based on the evidence presented by the prosecutor’s office. Consequently, it handed Wali a 6-month imprisonment sentence, a 10,000 Egyptian pounds fine for each infringed work, and accorded Kurasov 100,000 Egyptian pounds in damages. The court explains that the evidence presented was sufficient for it to reach this conclusion and underlined that Kurasov, as a Russian national, benefits from Copyright protection in Egypt pursuant to article 139 (1) of the ECL since Russia is a Member State of the World Trade Organization.

Commentary & Conclusion

Kurasov v. Wali underscores the importance of acknowledging original works and the perils of crossing the fine line that separates inspiration from imitation.

It is safe to assume that both artists were inspired by Egyptian art and its pharaonic heritage as found on the walls of many ancient tombs and temples. Also, it is equally safe to assume that both artists have the propensity to express their originality and brush strokes in a Picasso-like cubist technique. Thus, it is highly plausible, if not evident for some, that this case can fall more within the boundaries of inspiration and not pure imitation of protected artwork. Yet, the court failed to grapple with this topic and missed the opportunity to articulate a workable standard for distinguishing original works and transformative uses from pre-existing art works.

The larger question of demystifying the line between inspiration and imitation in art works under Egyptian law must unfortunately await the Court of Appeal’s decision and the latter should not shy away from delving into the resemblances of both art works to reach a more detailed, thorough, and well-reasoned verdict.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.