Since 22 May 2024, Meta has notified to European users of Instagram and Facebook – through in-app notifications and emails – an update of its privacy policy, linked to the upcoming implementation of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in the area.

Indeed, the company already developed and made available some AI features and experiences in other parts of the world, including an assistant called “Meta AI” (here and here), built on a large language model (LLM) called “Llama” (here and here), and, in an official statement, announced the imminent plan to expand their use also in Europe.

This initiative resulted in some pending privacy disputes, which polarized the debate. However, data appear to be just one side of the medal and to conceal much deeper copyright concerns. Given the holistic approach required by the challenges related to the construction of AI models, it is appropriate to proceed in order, starting with a broader overview.

The new Meta’s privacy policy

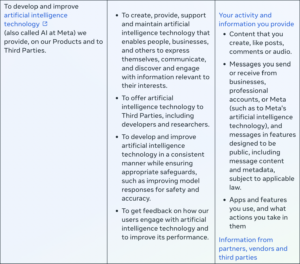

According to the new privacy policy, which will come into effect on 26 June 2024, Meta will process, in particular, activity and information provided by users – including content created, like posts, comments or audio – to develop and improve AI technology provided on its products and to third parties, enabling the creation of content like text, audio, images and videos. Legitimate interests pursuant Article 6(1)(f) of the General Data Protection Technology (GDPR) are invoked as legal basis.

A complementary section specifies that a combination of sources will be used for training purposes, including information publicly available online, licensed information from other providers and information shared on Meta’s products and services, with the only explicit exclusion of private messages with friends and family.

The privacy policy of WhatsApp does not seem affected, even if new AI tools are in development also for this service. The same seem to apply to the general terms of use.

The right to object

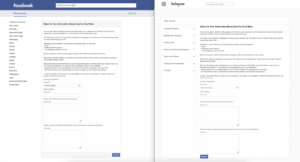

The user has the right to object to information shared being used to develop and improve AI technology. For this purpose, the user is required to fill in an online form accessible from a link – “right to object” – placed at the top of the privacy policy (here, at the moment, for Facebook and for Instagram). The forms appear available only after the log-in and only within EU.

Interestingly, failure to provide a motivation, even if it is requested as mandatory, does not seem to undermine the acceptance of the request, which – as the author was able to verify – is generally confirmed by email within a few seconds. In any case, such opt-out will be effective only going forward and some data could still be used if the user appears in an image someone shared or is mentioned in another user’s posts or captions.

The user will be able also to submit requests in order to access, download, correct, delete, object or restrict any personal information from third parties being used to develop and improve AI at Meta. For this purpose, the user is required to provide prompts that resulted in personal information appearing and screenshots of related responses.

The privacy disputes

The mentioned notifications apparently followed a number of enquiries from the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC), which slowed down – but did not block – the launch of the initiative.

Against this background, on 4 June 2024, the Norwegian Data Privacy Authority raised doubts about the legality of the procedure.

On 6 June 2024, NOYB, an Austrian non-profit organization focusing on commercial privacy issues on a European level, filed complaints in front of the authorities of eleven European countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland and Spain). It alleged several violations of the GDPR, including the lack of legitimate interests, the vagueness of the terms “artificial intelligence technology”, the deterrence in the exercise of the right of object, the failure to provide clear information, the non-ability to properly differentiate between subjects and data and the irreversibility of the processing. Consequently, it requested a preliminary stop of any processing activities pursuant Article 58(2) GDPR and the start of an urgency procedure pursuant Article 66 GDPR.

On 10 June 2024, Meta released an official statement underlining the greater transparency than previous training initiatives of other companies and pointing out that Europeans should “have access to – or be properly served by – AI that the rest of the world has” and that “will be ill-served by AI models that are not informed by Europe’s rich cultural, social and historical contributions”.

On 14 June 2024, the Irish DPC reported the decision by Meta to pause its plans of training across the EU/EEA following intensive engagement between the authority and the company.

On the same day, NOYB responded by emphasizing the possibility of Meta to implement AI technology in Europe by requesting valid consent from users, instead of an opt-out. Moreover, it underlined that, up to that point, no official change has been made to Meta’s privacy policy that would make this commitment legally binding.

At present, therefore, the case appears at a standstill.

The copyright concerns

Meanwhile, beyond the privacy issues, authors and performers worldwide – the driving force behind such services – are protesting to the new AI policy of Meta. Many threaten to leave the platforms, even if abandoning the social capital accrued on these services could represent a major obstacle. Others propose the use of programs which adopt different techniques to obstruct the analysis of the works and the training of AI technologies, such as Nightshade and Glaze. Moreover, platforms that are openly antagonistic to AI are gaining attention, such as Cara, which does not currently host AI art, uses a detection technology to this purpose and implements “NoAI” tags intended to discourage scraping.

Even other internet service providers are currently facing similar issues and had to provide certain clarifications. For instance, Adobe, after some uncertainty on the interpretation of its updated terms of use which provided for a license to access content through both automated and manual methods, has recently clarified (here and here) that their customers’ content will not be used to train any generative AI tools and confirmed its commitment to continue innovation to protect content creators.

Last month, instead, Open AI, which is defendant in some pending copyright infringement claims, published its approach to data and AI, affirming the importance of a new social contract for content in the AI age and announcing the development by 2025 of a Media Manager, which “will enable creators and content owners to tell [OpenAI] what they own and specify how they want their works to be included or excluded from the training” (see, for an analysis on this blog, Jütte).

All this appears to be part of a growing lack of trust of authors and performers surrounding tech companies and their AI tools, as well as a strong demand for guarantees. While the development of AI technologies can result in important creative instruments, the question of the fair consideration of the interests of authors and performers of the underlying works, including their remuneration through digital media and the sustainability of creative professions, remains open.

To escape this interregnum, a new balance is needed. Perhaps it is time to restart from copyright fundamentals and, in particular, who the system is intended to protect. If the answer will be authors, then only a few superstars or even the remaining vast majority? The risk is intellectual works to be considered just data – as this affair seems to emphasize – and authors and performers to be mislabeled as mere content creators.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.