Introduction

This two-part blog post is aiming to explain what Rights Retention is and how it works in practice. In the first part, I’ll explain the forces at play in the publishing industry, why copyright ownership in academia is so important and how the publishing process works. These are technicalities that must be explained beforehand for readers to easily understand the second part, in which I’ll explain how rights retention strategy was designed and implemented to limit the power differential between academic publishers and research funders and universities. I will also examine the effects of implementing this strategy.

Background

The academic publishing industry is, just like all other industries, an infinite game. The sole purpose of a participant in an infinite game is to stay in the game and to continue to play it. The best examples of infinite games are business and politics: whether you win or lose, as long as you are relevant in the game, you’re doing just fine. The rules are fairly open: there is no start or end of the game, players can join or exit at any time, each player can decide their own strategy and so on. A contrario, a finite game has fixed rules that cannot change during the game, there is a time limit and at the end there is a winner and one or more losers. The sole purpose of engaging in a finite game is to win it. Sports are the best examples of finite games.

Over the last few decades, publishers have been criticised for systematically undermining the purpose of copyright by redirecting the benefits of the legal protection towards themselves instead of the intended beneficiaries – authors and the public. This is why access to scientific journals and academic publishing has become unsustainably expensive, while publishers have amassed incredible profits.

Major publishers are profit driven commercial companies, flexible enough to adapt and innovate when market conditions are changing; they are united, and their employees are generously financially motivated.

Universities and research funders have only recently managed to coordinate and present a united front in their dealings with academic publishers to finally bring some balance to the game. But it seems a most precarious balance. In the UK, there are over 150 universities whose researchers are often at odds with their employers for a multitude of reasons. This situation makes universities quite hesitant to change the status quo, unless the change is radical enough to make both employees and management happy and willing to accept it.

Nevertheless, the interests of universities and research funders are aligned for the moment. They both want cheaper (perhaps even free) access to research, albeit for different reasons: universities need it for teaching and further research, while funders, whether public or private, measure their success by the number of lives improved by the research they are supporting – which cannot be achieved when research is hidden behind a publisher’s paywall. Consequently, research funders are setting up requirements for grant beneficiaries demanding that the research they are supporting be made available open access. Publishers have reacted by adjusting their copyright policies in such a way that open access can only be achieved by paying extra (an article processing charge – APC), which authors and universities can’t afford, and research funders are reluctant to pay as they would rather use the money to support (more) research. Navigating the Machiavellian labyrinth created by the convergence of the publishers’ policies with research funders and universities’ demands would give pause to Ariadne herself. This escalation has increased the general confusion and bureaucracy, as well as the overall costs of research.

It is in this context that cOAlition S – an organisation whose members are EU national research funders as well as private and public funders – “developed Plan S whereby research funders will mandate that access to research publications that are generated through research grants that they allocate, must be fully and immediately open and cannot be monetised in any way”. The objective is to stop academic publishers from reaping the benefits of research done by academics employed by universities and financed by public and private funding.

The old argument of copyright ownership in academia

According to the UK’s Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, the author of a work is the owner of any copyright in it. If the work was created by an employee in the course of their employment, their employer is the first owner of any copyright in the work, subject to any agreement to the contrary.

This rule applies to all domains of economic life in the UK, except academia. In Rahmatian’s view, the answer to the question who owns the copyright in research outputs created during employment by academics depends on whom you ask: academics and their unions will say that it is the employee-author of the work who owns the copyright. Unsurprisingly, there are countless scientific articles explaining why this should be the correct answer. According to Waelde et al., “There is a statutory presumption that, where a name purporting to be that of the author appears on copies of a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work, when published, or when made, the person whose name so appears is the author of the work, and that the work was made in circumstances not involving that person’s course of employment, Crown or parliamentary copyright, or the copyright vested in certain international organisations. Like any presumption, this may be rebutted by contrary proof.”

At the same time, as the universities are coming to realise the importance of copyright (and of IPR in general) as economic assets, they are starting to think about how to claim it. In the management’s view, it is the university as employer who owns the copyright in research outputs created by their academic employees. After all, section 11(6) of Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 is pretty clear.

In practice, the universities have never claimed copyright in the works created by academics during employment (as it could possibly escalate and fuel the next industrial conflict) allowing authors to sign publishing contracts in a personal capacity. Both sides are diplomatic enough not to escalate the argument, even though the current status quo hurts them both and favours the academic publishers.

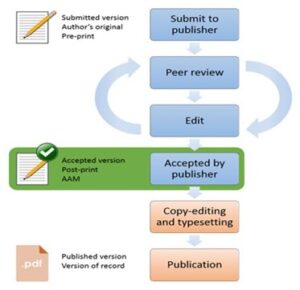

The publishing process

The submission of scholarly works is usually online, a step-by-step process that cannot be interrupted or negotiated in any way. For works with multiple authors, publishers will ask corresponding authors to assign copyright in the work (through a publishing contract) during the submission process under the condition that if the output will not be accepted for publication, the copyright will revert to the authors. More traditional publishers will require authors to assign copyright after the peer-review process. In most cases, the publishing contract can be considered an adhesion contract, as the academics’ lack of interest in reading the terms of the contract is only matched by the publishers’ reluctance to change it. Another important point to highlight is that, during submission, publishers will ask the corresponding author to confirm that they have obtained permission from their co-authors (or joint authors) for publishing the work; in practice there is no written agreement from co-authors or joint authors. Whilst they all know that the work will be published in a scientific journal, as this is the whole point of the collaboration and it is expected to happen, there is no written agreement.

All scientific journals rely on the peer-review process: this is how the chaff is separated from the wheat and the quality of the journal is ensured. After submission, the work will be sent for assessment to independent experts in the relevant field, who will judge the validity, significance and originality of the work. These are usually academic researchers employed by other universities.

Following this assessment, there may be some comments or changes suggested by the peer-reviewers that will be discussed by the editor with the author. Some or all of these comments and changes may be included in the work after which it will be formally accepted for publication. This version of the work is usually named author accepted manuscript (AAM).

The next step is about applying the copy-editing and typesetting processes specific to each publisher. In this way, all images, maps, or graphs will be set in the corresponding page and all typographical arrangements will be applied to make this version of the work recognisable as a work published by the specific scientific journal.

The very last step of the process is the publication of the work. This can be online or in print or both. Usually, the online publication date is ahead of the print one. The published version is usually called the Version of Record (VoR).

It is worth mentioning that there will usually be minimal differences in content between the submitted version of the article, the AAM and the VoR. Any changes addressing the comments of the peer-reviewers, if there are any and if they are included, will represent the distinction between the submitted version and the AAM, while copy-editing and typographical arrangements will make up the distinction between the AAM and the VoR.

Disclaimer

This blog is provided for general information only. It does not constitute legal or other professional advice or seek to be an exhaustive statement of the law and should not be relied on. You should take specific legal advice on any particular matter which concerns you.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.