In Anglosphere nations, the rights of creators are governed almost entirely by their contracts with investors. The US and Canada have the only (small) exceptions: US law entitles creators to terminate (most) agreements after 35 years; in Canada, rights revert automatically to heirs 25 years after the author’s death. Outside those cases, and throughout the UK, Australia and New Zealand, contracts are king.

In Anglosphere nations, the rights of creators are governed almost entirely by their contracts with investors. The US and Canada have the only (small) exceptions: US law entitles creators to terminate (most) agreements after 35 years; in Canada, rights revert automatically to heirs 25 years after the author’s death. Outside those cases, and throughout the UK, Australia and New Zealand, contracts are king.

This contrasts with elsewhere in the world, where countries have enacted a variety of statutory provisions designed to protect creators in their dealings with cultural investors such as publishers or record labels. Some of those rights were designed for the digital world, such as the 2014 French law governing publishing contracts. Among other things, it gives book authors an entitlement to recover their copyrights if their book has been published at least four years, and they haven’t been credited royalties for at least two. But many others predate the digital era. They don’t reflect the reality of creators having so many more options for distributing their work than in the analogue era, and so fail to take advantage of the new possibilities reversion offers in the digital era – to not only help creators get paid, but to simultaneously help us reclaim lost culture.

Growing awareness of those new possibilities are making reversion a hot topic in copyright. We have tangible evidence of that in the requirement of article 22 of the EU Digital Single Market Directive for member states to give creators entitlements to reclaim unexploited rights. But rightsholders have been pushing back as well. It’s not unusual for them to claim that there’s no need to implement new author rights – it’s all taken care of by the contracts.

We set out to investigate that claim. Several English-language studies had analysed publishing contracts in the late 20th century, and their findings suggested publishing contracts were not adequately safeguarding author interests. But the most recent such study took place in 1991. We wanted to get a sense of how these trends have developed since, particularly as we transitioned into the digital era.

What we did

To do this, we used content analysis methods to examine a sample of 145 book publishing contracts spanning 1960 to 2014 from within the archive of the Australian Society of Authors (ASA). We reviewed the contracts under strict terms of confidentiality, did not collect personal information, and note that our results do not necessarily reflect the ASA’s views.

The contracts within the archive itself are not necessarily representative of publishing contracts in Australia or all contracts received by the ASA, and our sample itself was not necessarily representative of the contracts in the archive. Nevertheless, it gives us some idea of actual terms that have been offered by publishers to authors, and how they have changed over time. Since the publishing industry is so global, our findings are likely to be broadly applicable in other English-language markets too, particularly the UK.

A sneak peek at some key results

1. Publishing contracts are extremely broad.

83% of the contracts took the author’s rights to publish, print and license the work for at least the entire copyright term. In fact, 19% of the contracts took rights for the entire term and any future copyright term. This meant those publishers obtained the benefit of the 20-year term extension that was legislated in Australia in 2006. The rights taken also tended to be very broad, frequently taking global rights and nearly half taking rights in all languages. That makes appropriately drafted reversion clauses particularly important.

2. Out-of-print clauses lacked clear thresholds for authors to exercise them.

Out-of-print clauses are the most common reversion right in publishing contracts. They were originally designed to give authors the opportunity to regain their rights if a publisher is no longer willing to invest in them. In the analogue era, a publisher’s willingness to make the sizable investment that was required by a new print run was a proxy for that. Later, out-of-print was sometimes replaced by other measures, such as whether the book was ‘available in any edition’.

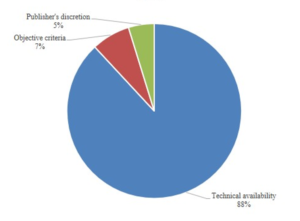

Such standards are fuzzy, and since the 1960s author organisations have been advocating that they be replaced by clear thresholds – for example, deeming a book to be out of print if it generated below $200 in royalties or sold fewer than 100 copies in the previous year. These calls became much more urgent as we entered the digital era, in which the availability of digital publishing and print on demand can mean no book is ever truly ‘unavailable’. Despite all that, of the contracts with out-of-print clauses we analysed, we found just 7% contained such an objective standard. 88% used technical availability measures like ‘out of print’, ‘out of print or off the market’, or ‘out of print and not available in any edition’. A further 5% left the determination of out-of-print status entirely to the publisher’s discretion.

Chart: What standard determines whether a book was out of print?

3. Few contracts provided for unused rights to return to authors.

Reversion clauses can also enable authors to reclaim unexploited rights (for example, foreign language rights or audiobook rights). Once again, such rights are becoming more important than ever, since digital distribution, recording and translation technologies are opening up new options for authors to exploit them. However, we found just 6% of contracts gave authors the right to reclaim unexploited rights.

Further reading

The full written paper sets out our method, full results and analysis of what these findings mean for future reform. See Are Contracts Enough? An Empirical Study of Author Rights in Australian Publishing Agreements by Joshua Yuvaraj and Rebecca Giblin, which has been accepted for publication by the Melbourne University Law Review and is now available on SSRN. This blog post draws from that paper and all sources can be found within it.

This research has been supported by funding from the Australian Research Council via projects LP160100387 and FT170100011, an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, and Monash University.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.