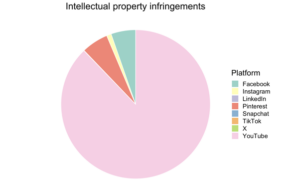

The Digital Services Act (DSA) transparency database, while proving to be rather useless for misinformation or hate speech researchers, is very enlightening on copyright moderation. Platform governance researchers have long suspected that YouTube is the most heavily moderated platform on copyright issues, and we now have concrete proof of this. YouTube, to date, according to the DSA transparency database has submitted over 946 000 content moderation decisions featuring intellectual property infringement in 30 days prior to July 27, 2024. This is more than any other VLOPs currently featured in the DSA database. The graph below illustrates the proportion of the content moderation decisions taken in one day based on intellectual property infringements that were taken by YouTube. (One Day in Content Moderation Report by PGMT lab is downloadable here).

However, research conducted under the HORIZON Europe project ReCreating Europe, and recently published in the Policy & Internet journal, suggests that YouTube’s disclosed figures may under represent the actual extent of copyright moderation. Our study focused on the effects of Article 17 of the EU Copyright in the Digital Single Market Directive (CDSMD) on copyright moderation practices, comparing Germany and France—two EU member states of similar size and population but differing in their timing of CDSMD implementation.

The first part of the study presents findings on copyright takedowns on YouTube in Germany and France between 2019 and 2022. To obtain these findings, we tested a subset of videos from the largest YouTube study (conducted by Rieder et al. in 2020) before assessing, first, whether they had been removed by YouTube and, second, how the removals were related to the countries in question, the video categories, and other predictors (such as likes and engagement). The first data set comprises a sample of 4,000,000 videos from EU-based YouTube channels. Based on this, we collected a second data set in 2022 after CDSMD implementation and filtered by countries (Germany and France). This second data set is a 2.09% subsample of the original data set, resulting in 83,676 videos. This allowed us to compare the incidence of video removals in both countries and examine the reasons provided by YouTube for these takedowns, such as copyright infringement complaints and account deletions.

Our findings indicate a significant underreporting of copyright-related takedowns, as many removals were attributed to “unknown reasons” or “deletion of associated YouTube account,” which we argue are often indirectly related to copyright moderation. This conclusion is supported by previous scholarship (e.g. Kaye & Gray, 2021) and YouTube’s own copyright enforcement mechanisms (YouTube Help, 2023), which can obscure the true reasons for content removal. In sum, this first assessment on the content level clearly shows massive underreporting of copyright-related takedowns by YouTube in the embedded information of removed videos. As we have shown, the label “Unavailability due to Copyright Infringement Complaint” is not a good proxy for assessing effects of copyright content moderation. There is a strong indication that many of the removals in both the “unknown reasons” and the “account deleted” categories are actually copyright-related.

To further assess the relation of copyright content moderation to removals for this underdefined content, we have developed additional statistical measures. For this, we used a random forest model to assess each variable that was important for takedowns. The model used variables derived from the video metadata provided by the YouTube API v3.

In our model, category ID was revealed as the most important predictor of videos being taken down for an “unknown reason.” Building on this result, we identified those categories that are most prone to copyright enforcement from the existing literature (e.g. Urban et al., 2017).

As a result, we argue that in addition to those videos earmarked as “Unavailability due to Copyright Infringement Complaint” it is reasonable to add videos with labels “unknown” or “account deleted” if and only if they have content categories associated with film, music gaming, sports and entertainment. In conclusion, our best effort estimate after this multistep assessment is that 2.17% of videos in our sample may have been taken down, both by the platform and by the users themselves, due to copyright content moderation.

This result sits right in the middle of existing scholarship on copyright-related takedown rates. While in Gray and Suzor’s (2020) study only approximately 1% of all uploaded videos had been removed due to apparent copyright violations, an analysis by Erickson and Kretschmer (2018) of videos highly susceptible to takedowns, such as parodies, revealed with 15.5% a far higher percentage of takedowns that might be copyright-related. The fact that Erickson and Kretschmer have this high estimate might not be surprising: with parody, they focused on content that is highly susceptible to copyright takedown. The difference between the estimate by Gray and Suzor and our own might be related to growing pressure and external regulation of platforms such as the CDSMD.

Based on this best-effort assessment of the role and scope of copyright content moderation in takedowns, we then compared the findings for the two different countries in the study (Germany and France) to test for potential early effects of CDSMD implementation on copyright content moderation.

The results show remarkable differences between Germany and France. In France, there have been more takedowns in general with 3,410 takedowns in comparison with 2,901 in Germany. Yet the relative share of copyright-related takedowns is much higher in Germany with almost two-thirds of takedowns (64.19%) being copyright-related in comparison with only a bit over a third (39.62%) in France.

To contextualize these results, it is important to note that national copyright regimes have always differed between France and Germany, so the implementation of CDSMD with regard to timing and substance is not their only difference—but in general, the copyright regimes in France and Germany had been harmonized on a quite high level already before the CDSMD (Sganga et al., 2023). Article 17 of the CDSMD, as highlighted by legal scholars (Husovec & Quintais, 2021), is not merely a “clarification” of the existing law, but it changes the law in fundamental ways. So, while longstanding differences in the copyright regimes of the two countries might cause different blocking behaviors, we consider the early German implementation of the CDSMD a more plausible explanation for the observed differences.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.