‘Please go!’ said pop group Golden Earring to their music publisher Nanada when they put an end to their publishing contract! As it sometimes happens in long-standing relationships, the once harmonious author/publisher cooperation had deteriorated to such an extent that a break-up was inevitable. Unfortunately, Golden Earring’s way of going about it brought both parties in front of the Supreme Court of the Netherlands. This is where a good publishing contract could have made a difference!

‘Please go!’ said pop group Golden Earring to their music publisher Nanada when they put an end to their publishing contract! As it sometimes happens in long-standing relationships, the once harmonious author/publisher cooperation had deteriorated to such an extent that a break-up was inevitable. Unfortunately, Golden Earring’s way of going about it brought both parties in front of the Supreme Court of the Netherlands. This is where a good publishing contract could have made a difference!

The facts

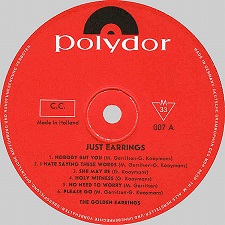

The contractual relationship between the parties goes back to 1971. While Golden Earring never complained about the quality of Nanada’s performance as a music publisher, the group eventually wanted to put an end to the relationship. By letter of 25 August 2010 Nanada was informed of the group’s decision to dissolve the agreement. Alternatively, the group offered Nanada the possibility to reach an agreement on how it would fulfil its obligations or pay damages. Failing this, the contract would be dissolved by 26 November 2010. A lack of trust in a fruitful cooperation was the motive invoked for dissolving the contract.

The Golden Earring’s publishing agreement operated a full transfer of rights on their songs to the publisher, for the entire duration of the copyright protection. In exchange for the transfer, however, the contract did not specify in any detail the nature or extent of the publisher’s obligations towards Golden Earring. Moreover, the contract did not provide for a termination clause. In practice, Golden Earring deemed the contract dissolved as of 28 August 2011. This action gave rise to the current dispute. Was the publishing contract legally dissolved?

The Court’s analysis

This matter essentially falls under general contract law, as the rules on authors’ contract law were introduced in Dutch legislation only after the start of the litigation. To solve the case, several issues must be addressed: 1) the property law effect of the contract, as a consequence of the transfer of rights; 2) the classification of the contract, e.g. of determinate or indeterminate duration; 3) the obligation to put the other party on notice; and 4) the need to invoke a serious motive for termination.

First, Nanada argues that the contract is not open for termination in view of the fact that it operates a transfer of property. The Supreme Court disagrees: the fact that rights are transferred poses no obstacle to the possibility to dissolve a contract. For the Court, the transfer of music rights is serviceable and inextricably linked to Nanada’s obligation to promote and exploit the works. However, it would be only fair and reasonable (see art. 6:248 of the Dtuch Civil Code) that the publishing rights transferred to Nanada revert to the authors upon termination of the contract.

The publishing contract stipulated that it would last for the duration of the copyright protection on the songs, e.g. 70 years post mortem auctoris. The Court further rules that the length of the publishing contract is so long that it amounts to a contract for indeterminate time. And, in principle, contracts for indeterminate time may be dissolved. The question is how, in absence of a termination clause? More specifically, were the members of the Golden Earring obliged to put Nanada on notice, pursuant to article 6:89 of the Dutch Civil Code, to allow it to remedy the complaint, so as to avoid the termination of the publishing contract? And did they need to provide evidence of a sufficiently serious ground for termination?

To both questions the Supreme Court answers in the affirmative. It is settled case-law that, in deference to the principle of reasonableness and fairness assessed in relation to the nature and content of the agreement and the circumstances of each case, termination may only occur in the presence of a sufficiently serious reason. Furthermore, Nanada should have been properly warned of the group’s dissatisfaction and given the chance to resolve the problem, before proceeding with termination.

It is interesting to note that even if article 25e of the Dutch Copyright Act had been deemed applicable, it would not have provided the Golden Earring any additional help in the circumstances. Whereas the newly introduced ‘non-usus’ rule does govern cases where the publisher fails to exploit the rights, it does require both a prior notice and a sufficient ground for termination.

In practice, the Dutch Supreme Court’s decision means that even with the support of the law, authors may not put an end to a publishing contract without following certain steps. The process would be easier, however, if the agreement itself foresaw in a proper revision or termination mechanism, especially if the contract is indeed meant to last that long. Nothing beats a well-written contract!

To make sure you do not miss out on posts from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe to the blog here.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.