This ruling, rendered by the IP specialist section of the High Court of First Instance of Paris, breaches the most basic EU and French copyright law, by refusing copyright protection to an obviously original photographic work. This very surprising ruling is unfortunately just another ruling contrary to the elementary rules of copyright law that has been given by the High Court of Paris.

This ruling, rendered by the IP specialist section of the High Court of First Instance of Paris, breaches the most basic EU and French copyright law, by refusing copyright protection to an obviously original photographic work. This very surprising ruling is unfortunately just another ruling contrary to the elementary rules of copyright law that has been given by the High Court of Paris.

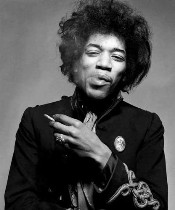

On 21 May 2015, the High Court of First Instance of Paris (Tribunal de Grande Instance) rendered a judgment in which it ruled that a famous photograph of Jimi Hendrix, taken by Gered Mankowitz, is not original and therefore not protected by copyright. The photograph is reproduced hereabove. The 3rd Chamber of Paris High Court, one of France’s nine courts specialising in intellectual property matters (with exclusive jurisdiction), has rendered several very worrying rulings of the same kind.

1. The judgment of the High Court of First Instance of Paris

In the present case, a French company that sells electronic cigarettes reproduced the portrait of Jimi Hendrix and used it for its advertisements, replacing Jimi Hendrix’s cigarette with one of its products, i.e. an electronic cigarette. The assignee of Gered Mankovitz’s rights had not been asked for authorisation.

In the brief filed before the Court, the rightholder explained the originality of this obviously original work, by presenting the author’s choices (thus complying with French and EU copyright law): ‘this extraordinary and rare photograph of Jimi Hendrix succeeds in capturing in a fleeting moment, the striking contrast between the lightness of the artist’s smile and the curl of smoke, as well as the darkness and the geometric rigor of the rest of the image, created in particular by the lines and angles of the torso and arms. The capturing of this unique moment and its enhancement by light, the contrasts and the narrow framing of the photograph on the torso and head of Jimi Hendrix, reveal the ambivalence and contradictions of this man who is a music legend, and make the photograph a fascinating work of great beauty which bears the imprint of the personality and talent of its author.’

The Court dismissed the plaintiff’s action, ruling that the plaintiff simply presented the aesthetic characteristics, and not those relating to the originality of the photograph, thereby placing the Court and the defendant in a situation in which a discussion on the originality of the work is not possible.

2. Reminder: the applicable rules – why the Paris High Court is in breach of elementary French and EU copyright law

Article L.112-1 of the French Intellectual Property Code (‘IPC’) protects ‘the rights of authors in all works of the mind, whatever their kind, form of expression, merit or purpose’, without giving a definition of originality. Article L.112-2 IPC gives an indicative list of works which states ‘photographic works and works produced by techniques similar to photography’.

French case law has defined originality as the expression of the personality of the author. This definition is in line with European case law, which validated the French concept of originality, in particular in Infopaq (Case C-5/08) and in Painer (Case C‑145/10), in which the European Court of Justice ruled that ‘As stated in recital 17 in the preamble to Directive 93/98, an intellectual creation is an author’s own if it reflects the author’s personality’ (paragraph 88). In line with EU case law, French copyright law protects works that are only relatively original (Supreme Court, 30 April 2014, 13-15517). Works such as adaptations and technical or scientific works are protected if the work is the result of personal choices made by the author. The French courts (and all the national courts of the European Union) must therefore take into account all the choices of the author, including his most simple choices.

As regards photographs, recital 16 of Directive 2006/116/EC on the term of protection of copyright states that a ‘photographic work within the meaning of the Berne Convention is to be considered original if it is the author’s own intellectual creation reflecting his personality, no other criteria such as merit or purpose being taken into account.’ And article 6 of that Directive provides that ‘Photographs which are original in the sense that they are the author’s own intellectual creation shall be protected in accordance with Article 1. No other criteria shall be applied to determine their eligibility for protection.’

Most photographs are original, since the photographer has to choose the framing, the lighting, the time of the shooting, the moment of realisation, the focal length, the camera, the settings of the camera, etc. In a case concerning photographs of works of art for a catalogue, the Court of Appeal of Paris stated that each of these choices reveals the personal contribution of the author and his personality (27 January 2010, 08/04978), i.e. the author’s ‘own intellectual creation’. This position is in line with Painer, in which the European Court of Justice stated that:

In the preparation phase, the photographer can choose the background, the subject’s pose and the lighting. When taking a portrait photograph, he can choose the framing, the angle of view and the atmosphere created. Finally, when selecting the snapshot, the photographer may choose from a variety of developing techniques the one he wishes to adopt or, where appropriate, use computer software.

Mankovitz’s photograph of Jimi Hendrix is therefore original, and the choices stated in Painer were sufficiently explained by the plaintiff, i.e. framing, light, contrasts, positioning of Jimi Hendrix, moment the photograph was taken, etc. (see above (1) the plaintiff’s explanations).

Since the High Court of Paris could not rule that Mankovitz’s obviously original photograph is not original, it disingenuously ruled that the plaintiff did not present the case as it should have been presented. As the French say: ‘Qui veut noyer son chien l’accuse de la rage’ (‘When you want to kill your dog, you accuse it of having rabies’).

3. What now?

The real problem is that this ruling is not isolated. Such judgments have been handed down far too frequently by the High Court of First Instance of Paris, which often takes into account other criteria such as merit and purpose, in breach of articles 6 of Directive 2006/116/EC and L.112-1 IPC, without expressly admitting it, in order to refuse to afford protection to photographs that are undoubtedly original, to the extent that a symposium was organised by university professors and lawyers on this very problematic and worrying issue (Symposium: L’originalité en photographie, published in 70 RLDI (Kluwer) 103 (2011)).

And this does not only concern photographs (see Brad Spitz, Le droit d’auteur en France : un monopole menacé?, 94 RLDI (2013)). For example, in 2013 the High Court of Paris (13 June 2013, No. 11/18096) ruled that a book about tarot of several hundred pages is not original and therefore cannot be protected by copyright: it found, in breach of French and EU copyright law, that the book could not be protected because the subject (tarot) is not new (see Brad Spitz, Défaut d’originalité d’un livre: une décision contra legem de plus, 96 RLDI 14, No. 3178 (2013)). The court did not take into consideration the fact that the author had chosen and combined the words used to write the book. Of course, courts may not use novelty as a criterion for assessing the originality of a creation.

The Court of Appeal of Paris will certainly reverse the horrific judgment commented on here (and so afford protection to Mankovitz’s photograph), as it has done on many previous occasions. But the damage done to the victims and the very purpose of copyright law (justice, protection of property, innovation, investment, etc.) is tremendous. France, or at least Paris (the centre of most of France’s intellectual property infringement cases), can no longer be trusted as a jurisdiction to defend the fundamental rights of copyright owners. This is not acceptable in a democratic state. Moreover, France, though traditionally protective of authors’ rights, does not comply at present with its EU obligations as one of its supposedly specialised courts seems to completely lack the expertise needed to apply the basic rules of copyright law. Worse, many of these rulings actually seem to be due to the efforts of the High Court of Paris to dismantle EU and French copyright law, visibly with an ideological aim.

And what about the practical implications of the development of such case law for the exploitation of rights relating to photographs? For example, what are we going to do with the rights exploited via collecting societies and, in particular, the resale right (‘droit de suite’)? Will it now be impossible for the rightholders and collecting societies to collect royalties without first having obtained an enforceable judgment stating that the photographic work is original? With a decision like that of 21 May 2015 discussed here, collecting societies should theoretically have to prove in court that the photographs are original before they are allowed to claim any royalties. Should the French lower courts persist in that direction, it will no longer be possible to consider that works such as artistic photographs, or even music, are obviously original; collecting societies will then not be able to rely on a presumption of originality to collect royalties.

It is essential that things return to normal in France, and fast.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.