Decision of the German Bundesgerichtshof of July 28, 2016, file no. I ZR 9/15: “Auf fett getrimmt” (“trimmed to the fat”).

In accordance with the CJEU decision in Deckmyn v. Vrijheidsfonds/Vandersteen (C-201/13), the Bundesgerichtshof (“BGH”) as Germany’s highest civil court supported a broad interpretation of the term “parody” in its recent decision “Auf fett getrimmt”, thereby diverging from the more restrictive interpretation previously established under German case law. In addition, the BGH further shaped the weighing up of competing interests, an exercise which is necessary according to the CJEU.

Background

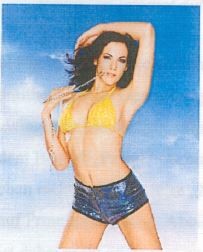

In the case at hand, the claimant was the photographer of the photo displayed below:

The photo shows a famous German actress, who was not involved in the case.

The photo shows a famous German actress, who was not involved in the case.

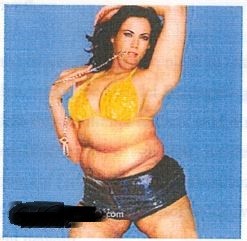

The defendant, a newspaper publisher, did not make available the original photo on its website, but rather a revised version. The photo was the result of a feature by the newspaper in which they made celebrities look different from the usual ideal of beauty and used Photoshop or other means to make them gain weight. The result was an edited photo, in which the actress’s photograph was edited to show her as fat, hence the name of the case:

The applicant claimed that making available the latter photo to the public infringed his copyright in the original photo and demanded financial compensation. While the court of first instance (District Court Hamburg, decision of 4 December 2014, file no. 5 U 72/11) had partially allowed the request, the appellate court (Court of Appeal Hamburg, decision of 25 February 2011, file no. 310 O 233/10) rejected the claim.

The Court of Appeal held that the claimant´s copyright had not been infringed, on the basis that the defendant was permitted to use the photo as a parody under the German principle of free use (“freie Benutzung”), § 24 (1) German Copyright Act. This provision allows a use even without the permission of the rights holder under certain conditions.

To assess these conditions for the case at stake, the Court of Appeal had applied the prior case law of the BGH. According to this prior case law, a free use can be held in two general scenarios (see also BGH paras. 19 et seq):

- Firstly, free use applies when the original work only served as an inspiration for the new work and the (copyright protected) characteristics of the primary work have faded away (“sind verblasst”). This is also called the “Blaessetheorie” (“fading away theorie”). This theory, however, could not be applied in the case. The original photo did not fade away, but made a clear reference to the original photo.

- Secondly, a free use can also be found if the old work is still recognisable but there is a sufficient “inner distance” (“innerer Abstand”) between the works in question (see further for example BGH, decision of 11 March 1993, file no. I ZR 263/91 – Alcolix; BGH, decision of 20 March 2003, file no. I ZR 117/00 – Gies-Adler). In order to establish a free use it is necessary that as a result of the use of the original work, a new work is created that could receive copyright protection on its own. According to established German case law, such an inner distance can appear for example in cases of an antithetical statement to the original version (“antithematische” Behandlung) and therefore, in particular, in cases of parodies such as the one in the instant case.

The BGH decision

The BGH held that the Court of Appeal had failed to give sufficient weight to CJEU case law on the interpretation of the concept of parody in the case at hand and, in this context, expressly referred to the recent CJEU judgment in Deckmyn v. Vrijheidsfonds/Vandersteen (CJEU C-201/13 of 3 September 2014). German law has not specifically implemented Article 5 (3) lit k) Copyright Directive 2001/29, which contains the parody exception on the EU level. Rather, the German legislation has relied on the longstanding case law in Germany, which dealt with parody cases under the aforementioned general free use exception of § 24 (1) German Copyright Act.

According to the BGH, for the assessment under § 24 (1) German Copyright Act, the term “parody” had to be defined in light of the exception of Article 5 (3) lit k) Copyright Directive 2001/29. Since the directive itself makes no express reference to the law of the Member States for the purpose of determining the meaning and scope of the concept of parody, it must be regarded as an autonomous concept of EU law and therefore must be interpreted uniformly throughout the EU, as the CJEU ruled in Deckmyn v. Vrijheidsfonds/Vandersteen (BGH para. 24).

In the aforementioned case, the CJEU upheld a wide interpretation of the term “parody”. To assess whether a parody can be assumed or not, the CJEU developed a two-step approach:

- In a first step, the term “parody” must be determined by considering its usual meaning in everyday language while also taking into account the specific context in which it occurs and the purpose of the rules of which it is part (CJEU para. 19). With respect to the usual meaning of the term, it is not apparent either from the usual meaning in everyday language or from the wording of Copyright Directive 2001/29 that a parody should satisfy certain conditions so as to display an original character of its own. According to the CJEU, a parody does not need an original character, other than that of displaying noticeable differences with respect to the parodied work. Moreover, it is not necessary that a parody can reasonably be attributed to a person other than the author of the original work, nor must it relate to the original work itself or mention the source of the parodied work (CJEU para. 21). Therefore, the term “parody” must be interpreted broadly, for the essential characteristics of a parody are simply the evocation of an existing work while being noticeably different from it and containing an expression of humour or mockery (CJEU para. 20).

- In a second step, conflicting interests must be weighed up in order to achieve a fair balance between the rights of holders of copyright and related rights on the one hand, and the freedom of expression of the user of a protected work who is relying on the exception for parody, on the other hand (CJEU para. 27). For the purpose of determining whether, in a particular case, the exception strikes a fair balance, all the circumstances of the case must be taken into account. Moreover, if the parody conveys a discriminatory message, which is for the national courts to assess, attention should be given to the principle of non-discrimination, based on Article 21 (1) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. This is due to the fact that the rights holder has a legitimate interest in ensuring the work protected by his copyright is not associated with a discriminatory message and does therefore not infringe any rights of third parties (CJEU paras. 30, 31).

In the case at hand, the BGH ruled that the edited photo fell within the definition of parody (first step CJEU). It still reminded a viewer of the original picture, but at the same time noticeably differed from it. As all the essential elements from the original work had remained, the depicted actress could still have been recognised despite the phototechnical editing of her bodily proportions (BGH para. 28 et seq.). Furthermore, the Court of Appeal would have been entitled to assume that the picture was an expression of humour or mockery since the popular ideal of beauty would have been caricatured. In contrast to former national German case law, the BGH did not require a parody to be “antithetical”, i.e. the humour or mockery being directed at the original, (although the BGH thought that this was the case; BGH para. 33). A mere mockery of something other than the original work would be sufficient (BGH para. 35). Finally, the BGH also dropped the prior requirement for a legal parody: that the parody needs to be a new work that could receive copyright protection on its own (see above). According to the CJEU, a parody does not need an original character, other than that of displaying noticeable differences with respect to the parodied work, so the BGH also lowered its test to the level of the CJEU (BGH para. 28).

Concerning the CJEU’s second step, according to the BGH, the Court of Appeal did not adequately weigh up the interests involved and failed to take into account all factors relevant to the circumstances of the case as is necessary according to EU case law (BGH para. 36 et seq.). In this context, the BGH made clear that according to the CJEU, the interests of the author and of the users had to be taken into account. Here, the BGH took the opportunity to further shape the CJEU’s concept:

- The BGH held that an antithetical use of the original in the parody – although not a condition for a parody – would speak heavily in favour of the user’s interests in free speech and freedom of opinion (BGH para. 38). Consequently, the old BGH concept of inner distance of parodies in cases where they contain humour or mockery directed against the original can live on.

- Furthermore, the BGH followed the CJEU’s view that the author can also rely on a possible infringement of third parties’ rights — for example in this case, the personality right of the pictured actress. But the BGH thought that such rights were not infringed, as it was clear to the public that the photo had been manipulated and did not represent the real state (BGH para. 40).

- Finally, also with regard to third party rights invoked by the author, the BGH tried to interpret and take further the CJEU’s statement that, if the parody conveys a discriminatory message, attention should be given to the principle of non-discrimination. The BGH held that this could not be interpreted in the sense of a “political correctness control” by the courts (BGH para. 39). Rather, the BGH emphasised the weight of freedom of expression. Not every parody affecting justified interests would be relevant, but only such parody that (1) infringes third party rights and (2) creates a justified interest of the author not to be connected with such a third party right infringement (BGH para. 39).

In conclusion, the BGH set aside the judgment of the Court of Appeal and referred the case back to that court. It now remains to be seen whether the Court of Appeal will still rule that the principle of free use applies in the case at hand, bearing in mind the interpretation of the concept of parody as established in Deckmyn v. Vrijheidsfonds/Vandersteen and further shaped by the BGH.

Comment and outlook

In summary, the new definition of the term “parody” developed by the CJEU is much broader than the old definition created under German law. As defined by the CJEU, a parody needs solely to evoke an existing work while being noticeably different from it and constitute an expression of humour or mockery; a sufficient inner distance between the works in question is not required.

However, the CJEU’s broad definition of the concept of parody appears to be not without problems, particularly in complying with the CJEU’s requirement that a fair balance be struck between the rights of the holder of a copyright and the freedom of parody of the user of the protected work. Of course, the right of the copyright holder must be protected, which it can be through a balancing of interests in which all circumstances of the individual case can be taken into account. However, a balancing of interests may well create legal uncertainty and potentially restrict the freedom of expression of the user of a protected work who is relying on the exception for parody. This particularly applies since the CJEU held that in order to achieve a fair balance between the conflicting interests the principle of non-discrimination based on race, colour and ethnic origin must be taken into account.

As parodies frequently deal with critical and controversial issues, there is a great risk that they may not be permitted under the principle of free use since they can often be regarded as an act of discrimination. Therefore, Courts’ consideration of potential discrimination in the context of interpreting the term “parody” risks an unjustified restriction of the freedom of parody.

Against this background, the BGH decision is a valuable clarification. The BGH seems to have been aware of the danger that the CJEU case law is abused to use copyright to cure politically incorrect parodies of any kind. The BGH underlined in its judgment Auf fett getrimmt that the freedom of parody is intended for the copyright good and that the importance of protecting parodies as manifestations of the freedom of expression must be borne in mind within the balancing of interests. The BGH made clear that copyright can only be invoked by the right holder in cases where the rights infringement, e.g. through discrimination, also runs contrary to the justified interest of the right holder not to be connected with the third party right infringement. The CJEU case law must not be misunderstood as enabling a copyright holder to sue for third party rights infringement, without his own justified interests being harmed.

But there are other open questions remaining. In particular, they stem from the relationship between the parody exception as harmonised by EU law, and moral rights protection, which is not harmonised on the EU level, but remains a national issue. For example, the BGH left open whether the moral right to be named (§ 13 German Copyright Act) or the moral right to integrity (§ 14 German Copyright Act) step back in the case of a parody that is legal under EU law (BGH para 41). The correct result will probably be that, generally speaking, such national moral rights institutions may not change the legality of a parody. The weighing up of interests necessary for moral rights protection should in principle not result in a different outcome.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.