Introduction: digital exhaustion

Introduction: digital exhaustion

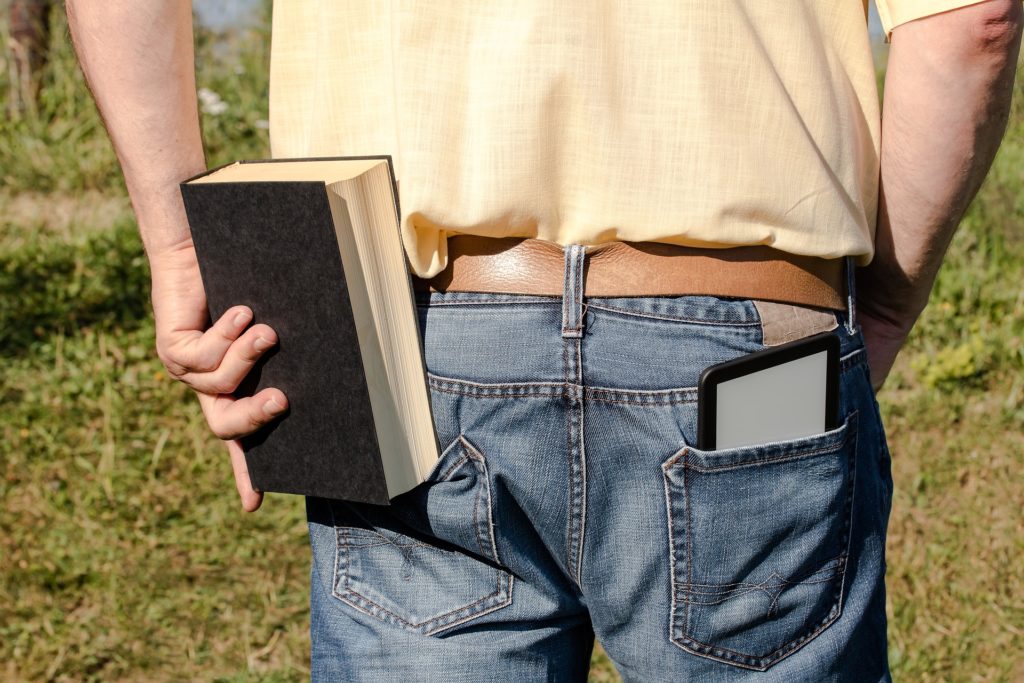

One of the main limitations to the right of distribution in European copyright law is the principle or rule of exhaustion. This rule, known as the first sale doctrine in US law, means that the right of distribution is exhausted by the first sale or other transfer of ownership of a copy of the work made by the rightholder or with his consent (Article 4(2) InfoSoc Directive). This rule has mostly been of straightforward application to physical copies of works, but can it be applied to digital copies of works too? That is the question in the case of Tom Kabinet in a nutshell.

Tom Kabinet is a Dutch company that aims to create a second-hand marketplace for e-books. It operates a website where you can upload used e-books and buy used copies of e-books. It started its business in 2015. Soon after, two organizations of publishers filed for a preliminary injunction to stop Tom Kabinet from selling used e-books. Tom Kabinet, however, believes it can rely on the CJEU’s ruling in UsedSoft and claims that there is digital exhaustion under EU law.

The story so far

The case started a couple of years ago when Tom Kabinet opened up a platform that allows people to sell their second-hand e-books. Publishers were unhappy with Tom Kabinet’s dealings and very quickly filed for a preliminary injunction. In its preliminary ruling, the court of Amsterdam did not impose an injunction, as it was unclear whether the resale of e-books is allowed under European Copyright law.

In the preliminary appeal, the Appellate Court of Amsterdam followed the district court’s ruling, but added that Tom Kabinet does not effectively prevent the sale of illegal copies through its platform. It therefore ordered Tom Kabinet to cease its activities until it applies effective methods to prevent this.

The Court of The Hague

After the preliminary procedure, the publishers went to the Court of The Hague for a ruling on the merits. The publishers claim first that offering the books for download infringes the right of communication to the public. The Court of The Hague did not agree, because there is no public, as only the person who buys the book can access it.

Second, the publishers argue that when Tom Kabinet copies a book to its servers it makes an unauthorized reproduction of the work. Even when Tom Kabinet sells an e-book, a copy of the work remains stored on its servers. The Court considered that, following UsedSoft, even if the right of distribution were exhausted, Tom Kabinet is not allowed to keep a copy on its servers after it has resold a copy.

Third, the publishers consider Tom Kabinet’s practice an infringement of their right of distribution. Tom Kabinet argued, in response, that the right of distribution is exhausted by the first legal sale. The Court, guided by the CJEU’s ruling in UsedSoft, found that there was a previous sale, although it held – contrary to Tom Kabinet’s claims – that the Computer Programs Directive is not applicable to e-books. It continued by explaining that under EU law it is unclear whether this would be allowed. After identifying several legal arguments for and against digital exhaustion of e-books, the Court of The Hague settled on three questions for the CJEU, which it argues must be answered even if it is considered that Tom Kabinet infringes the right of reproduction.

The first question is whether Tom Kabinet’s business actually involves the right of distribution under Article 4(1) InfoSoc Directive. In simple terms, does uploading for subsequent downloading by users in Tom Kabinet’s model mean distributing a work? If the answer is yes, it becomes relevant whether there is exhaustion of the right to distribution within the meaning of Article 4(2) InfoSoc Directive. The referring court asks whether the right to distribution is exhausted by the first sale of the e-book in the scenario at issue.

The other two questions relate to the right of reproduction. The first of those questions refers to the relationship between digital exhaustion and the right of reproduction in Article 2 InfoSoc Directive. The national Court wants to know whether, if there is in fact digital exhaustion in the terms above, it should be considered that there is consent to acts of reproduction necessary for the transfer of the lawfully acquired copy of the work between successive acquirers (and, if so, which conditions apply). The final question tackles the same issue, but from the perspective of Article 5 InfoSoc Directive, on exceptions and limitations. It asks whether the latter provision is to be interpreted as meaning that the copyright holder cannot object to the acts of reproduction necessary for the digital resale of exhausted copies of works and, if so, which conditions apply.

Considerations

The Court of The Hague considered that the InfoSoc Directive does not make clear whether intangible copies are also covered by the provisions on the right of distribution. It found indications in favour of and against a broader interpretation in the preamble of the Directive. It also noted that a tangible copy of a work can be considered functionally equivalent to an intangible copy, inviting the application of equal treatment, although it noted that tangible copies suffer from wear and tear, which might not apply directly to intangible copies. Finally, it found that the CJEU has not given an answer to these questions in in its previous judgments. With the Tom Kabinet case, the CJEU gets a clear chance to do so.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.