Introduction

Introduction

On 15 May, the Netherlands became the first EU member state to submit a complete DSM copyright directive transposition bill to parliament.[1] Both the timing and the content of the legislative proposal show an acute desire to avoid the risk of late or incorrect transposition.[2] In the operative provisions (auto-translate) and explanatory memorandum (auto-translate), the government has sought neither to mitigate the directive’s limitations nor to offer original interpretations of its impossible compromises. This deliberate lack of imagination is arguably a quality and, while not without its own risks and drawbacks, is based on a pragmatic assessment of national legislators’ room for transpositional manoeuvre. As such, it represents an interesting precedent for other member states considering their own transposition options in the twelve months remaining until the deadline of 7 June 2021. Moreover, despite its best intentions, the Dutch transposition proposal still manages to contain a number of notable choices, and court a number of notable controversies – some of which will probably require amendment in the course of the legislative process.

This three-part post provides a brief overview of the process that preceded the submission of the transposition bill, and a high-level description and analysis of its main elements – focusing on choices and interpretations that may be of interest to non-Dutch readers, in particular in relation to the provisions on press publishers’ rights and the liability of online content-sharing service providers (OCSSPs). The provisions in relation to new exceptions and limitations, extended collective licensing, and exploitation contracts are somewhat less contentious, but nonetheless require separate consideration. This Part 1 describes the consultation process that preceded the formal submission of the bill, its general structure, and the provisions transposing Article 15. Part 2 discusses the provisions transposing Article 17(1) – 17(5). Part 3 analyses the provisions transposing the rest of Article 17, and contains a number of concluding remarks.

Consultation process

During the legislative process, the Dutch government was broadly supportive of the directive’s harmonising provisions on exceptions and limitations, and exploitation contracts, but opposed to the provisions on press publishers’ rights and online content-sharing services. It voted against the final proposal, stating (together with Luxembourg, Poland, Italy and Finland) that it did not strike the right balance between the protection of right holders and the interests of EU citizens and companies, and lacked legal clarity.

While Poland followed through on its opposition with an annulment action before the EU Court of Justice, the Netherlands set its mind to transposition. In July 2019, just six weeks after the directive was published in the Official Journal, the Justice Ministry published a draft transposition bill for public consultation. This draft contained a number of interesting choices and interpretations. For example, it relegated significant directive provisions to the explanatory memorandum, including the second half of the definition of “online content-sharing service provider”, the exclusion of OCSSPs from the E-commerce directive safe harbour, and the proportionality requirement of Article 17(5). At the same time, the explanatory memorandum echoed the German government’s statement that Article 17 “is aimed solely at those market-dominant platforms which make large quantities of copyright-protected uploads accessible and which base their commercial business model on such a practice, i.e. services such as YouTube or Facebook.” It went on to give specific examples of services which are excluded from its scope: “services such as Wikipedia, blogs and forums, software platforms such as Github, messaging services such as Whatsapp etc.” In relation to Article 15, the explanatory memorandum made it clear that information society service providers could “continue to copy hyperlinks with newspaper headlines, several words or very short extracts including thumbnail photographs from a press publication, without the prior authorisation of the publisher.”

The consultation attracted 57 responses from a range of stakeholders, including collective management organisations, publishers, producers, consumers and consumer rights groups, and a number of tech companies and groups. In keeping with the polarised nature of the debate on the directive, stakeholders from various sides generally argued that choices in the consultation draft which favoured them should be maintained, while choices which they considered unfavourable violated the directive and should thus be removed – thereby incentivising the government to remove what original elements its consultation draft had contained.

The structure of the proposal

The transposition proposal is difficult to read. Rather than transposing the directive into a separate law, or a separate chapter, the proposal amends existing legislation. Thus, Chapter I of the proposal contains amendments to the Copyright Act, Chapter II contains amendments to the Neighbouring Rights Act, and Chapter III contains amendments to the Database Act. Some amendments add entire provisions, while others add individual words or references to existing provisions.

The consequences of this approach are somewhat comical. Article 15 is transposed as a new neighbouring right, and requires the addition of, or changes to, some 15 provisions in the Neighbouring Rights Act.[3] Moreover, since a number of directive provisions affect both copyright and (some but not all) neighbouring rights, there are considerable duplications and cross-references. Thus, Chapter I adds new Articles 29c, 29d, and 29e to the Copyright Act to transpose Article 17; Chapter II adds an Article 19b to the Neighbouring Right Act, which transposes Article 17(1) for performances, phonograms, films, etc. and then declares that most (but not all) of the new Copyright Act provisions apply mutatis mutandis.

There are also potential advantages to transposing the directive through amendments to existing laws. Most importantly, integrating the directive into the existing conceptual framework ensures a level of coherence. While creating an entirely separate framework for e.g. press publications and OCSSPs would make for a superficially ‘cleaner’ law, its meaning would not be any clearer, and questions would quickly arise as to whether common concepts, such as ‘communication to the public’ and ‘citation’, mean the same thing as they do in existing laws (remember the longstanding question, ultimately answered in the negative by the CJEU in Reha Training, of whether the ‘communication to the public’ concept has different meanings in copyright and neighbouring rights). The integrated approach hopefully ensures that common concepts have a uniform meaning (at least until the CJEU tells us otherwise).

In short, figuring out what changes the transposition proposal brings about is arduous, and reading the amended legislation once the transposition passes will be a permanent challenge,[4] but it might be for the best.

Press publishers’ right

The transposition of Article 15 of the directive into the Neighbouring Rights Act is a mostly straightforward affair. The definition is lifted almost verbatim from Article 2(4) of the directive, and the operative provisions are transposed functionally. Article 7b(1) of the Act enumerates the exclusive rights conferred by the first sentence of Article 15(1). The government explains that the rights pertain only to certain online uses by information society providers, and says that this relates especially to so-called news aggregators and media monitoring services – phrasing which is slightly stronger than recital 54 (which lists news aggregators and media monitoring services as examples) but which does not totally exclude other types of service providers.

The exclusions for private or non-commercial uses by individual users, acts of hyperlinking, the use of individual words or very short extracts, and the use of works or other subject matter for which protection has expired, are listed in a separate Article 7b(2). In this respect, the Dutch transposition is more compatible with the directive than the approach taken by France, where the exclusion of hyperlinks and very short extracts has been transposed in the form of an exception, and the exclusion of private use and public-domain works has not been transposed at all.[5]

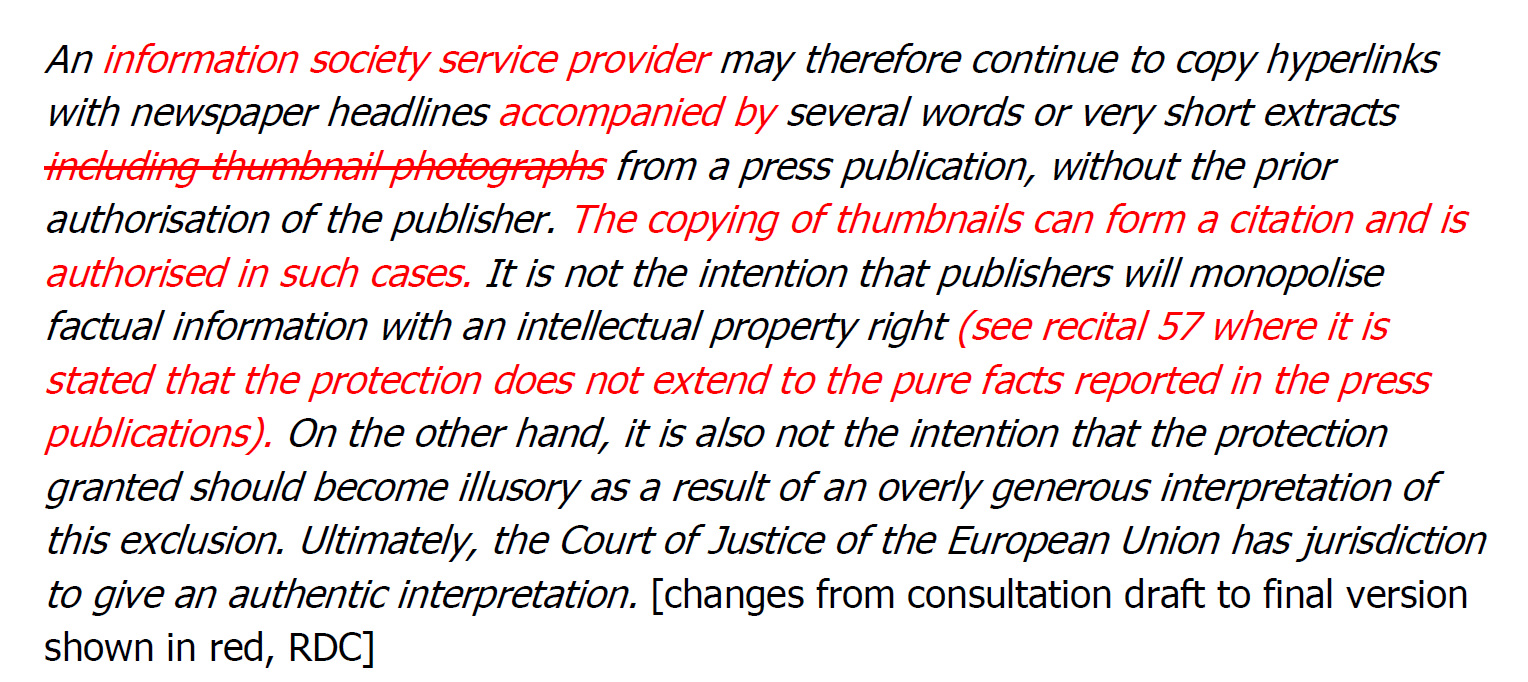

On the contentious issue of “very short extracts”, the government ultimately passes the interpretive buck to the CJEU. However, there has been a noticeable shift in the explanatory memorandum between the consultation draft and the final version, in particular as it relates to the use of thumbnail images:

In essence, the consultation draft suggested that “very short extracts” can include thumbnails, while the final version states only that thumbnails could be a quotation, and are allowed in that case. This might be read as suggesting that a thumbnail cannot be (part of) a “very short extract”, and that a thumbnail is only potentially permitted as a citation (if all the conditions are met), rather than being potentially out of scope of the publishers’ right entirely on the basis that it is a “very short extract”. Such a restrictive interpretation of “very short extracts” would be questionable. However, as the government recognises, the ultimate meaning of this impossible legislative compromise is anyone’s guess (and the CJEU’s unenviable prerogative).

Part 2 continues with a discussion of the provisions transposing the first half of Article 17 (OCSSPs).

[1] While France transposed Article 15 last year, and has another transposition proposal pending before its National Assembly, that proposal transposes only Articles 17 – 22 of the directive, thus omitting the new harmonised exceptions and limitations. See Communia’s Transposition Tracker for more details on the French proposal, and the status of transposition in other member states.

[2] This particular sensitivity to the risk of Francovich liability is due in large part to a 2018 court ruling holding the Dutch state liable for damage suffered by film producers as a result of the Dutch government’s public position – until it was negated by the CJEU’s ACI Adam judgment – that private copying from illegal sources was lawful.

[3] See the transposition table at the end of the explanatory memorandum.

[4] Dutch copyright lawyers are already used to this approach (the Copyright Act was called the Copyright Act 1912 until 2008, and is still based on the original numbering), and are resigned to their favourite laws being trashed even further when the Online Broadcasting directive (2019/789/EU) is transposed in similar fashion.

[5] The distinction between an exclusion from the scope of protection and an exception to that protection is significant not just doctrinally but also practically: the rightholder generally has the burden to prove a use of his protected subject-matter, while the user generally has the burden to prove his right to invoke an exception to that protection (including all applicable conditions). Moreover, the ability to invoke an exception might be limited by the three-step test.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.