In its landmark 1994 decision Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994), the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruled that Campbell’s creation of a rap parody version of a popular Roy

Orbison song could be fair use because it transformed the original song by adding something new, with a different purpose, or a new meaning or message. Since then, courts in the U.S. have grappled with how broadly or narrowly to interpret the concept of transformativeness when assessing fair use defenses to charges of copyright infringement. The Court in Campbell emphasized that transformative fair uses leave “breathing space” for next generation creations that build on the expression of pre-existing works. For the most part, courts have construed this concept broadly.

Starkly deviating from this trend was a Second Circuit panel decision in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 11 F.4th 26 (2d Cir. 2021) (hereinafter: Goldsmith). It reversed a lower court ruling that Warhol had made transformative fair use of a photograph that Lynn Goldsmith took of the rock musician Prince in 1981. It held that Warhol’s use was not transformative because the photograph was the “recognizable foundation” of the Warhol Prince Series. The panel abjured the “new message or meaning” test for transformativeness which the Supreme Court first announced in Campbell and reaffirmed in last year’s fair use decision, Google Inc. v. Oracle Corp. Am., 141 S.Ct. 1183 (2021).

In seeking Supreme Court review, the Foundation argued that the Goldsmith decision was inconsistent with the Court’s teachings in Campbell and Google. The Court will review that decision in the fall of 2022.

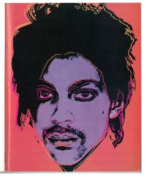

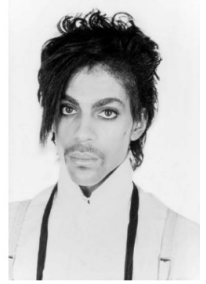

The facts of Goldsmith are straightforward. Vanity Fair decided to publish an article about the rock singer Prince in a 1984 magazine. Vanity Fair contacted Lynn Goldsmith’s licensing agency in search of a photograph of that performer to serve as an artist reference. The agency granted Vanity Fair a license to use a Goldsmith photograph of Prince for this purpose on a one-time-only basis. Vanity Fair then commissioned Andy Warhol to prepare an art work of Prince to accompany the article and supplied him with the Goldsmith photograph as a source material. Vanity Fair published the resulting colorful Warhol print of Prince in its magazine, crediting Goldsmith as its source (see here).

Many years later, after the tragic death of Prince in 2016, Vanity Fair decided to publish a special issue about him and contacted the Warhol Foundation about reusing the 1984 print for it. When Vanity Fair found out that Warhol had made additional prints based on the Goldsmith photo, it chose a different one to serve as the front cover of the special issue. Goldsmith saw the special issue and noticed that the cover was based on one of her photographs of Prince. She contacted the Foundation about her copyright claim, and then registered the photograph with the Copyright Office as an unpublished work.

Confident that Warhol’s use of the photograph was non-infringing, the Foundation sued for a declaratory judgment that Warhol’s prints were not substantially similar to Goldstein’s photograph and, alternatively, that Warhol had made fair use of the photograph. Goldsmith counterclaimed for copyright infringement. A trial court granted the Foundation’s motion for summary judgment on the fair use defense and denied Goldsmith’s cross-motion for summary judgment.

The trial court viewed Warhol’s Prince Series as transformative because, in keeping with Campbell, his works had a different meaning and conveyed a different message than Goldsmith’s photograph. The court emphasized the many artistic differences between Warhol’s prints and Goldsmith’s photograph, concluding that Warhol had taken no more than was reasonable in light of his transformative purpose. It noted that the Warhol Prince Series did not supplant market demand for Goldsmith’s photograph and, in fact, operated in a very different market than her photograph. Besides, Goldsmith had chosen not to license that photograph to others. Consequently, the market harm factor did not cut against Warhol’s fair use defense.

Goldsmith’s appeal met with success before the Second Circuit. The panel concluded that Warhol’s use of the Goldsmith photograph was not transformative. The panel regarded judges as ill-suited to make judgments about the meaning or message of works such as the Warhol prints. Nor should judges consider the artist’s intent or the views of art critics in deciding whether a secondary work was transformative. In its view, judges should instead look at the plaintiff’s and defendant’s works side-by-side and “examine whether the secondary work’s use of its source material is in service of a ‘fundamentally different and new’ artistic purpose and character such that the secondary work stands apart from the ‘raw material’ used to create it.”

The panel concluded that Warhol’s Prince Series “retains the essential element of its source material” and Goldsmith’s photograph “remains the recognizable foundation upon which the Prince Series is built.” At a high level of generality, moreover, it regarded the Goldsmith photograph and the Prince Series as “shar[ing] the same overarching purpose (i.e., to serve as works of visual art).” While not holding that Warhol’s Prince works were infringing derivatives, the panel suggested that they were closer to this category than to the transformative uses that courts had found to be fair.

Also weighing against the Foundation’s fair use defense, in the panel’s view, was that Warhol had “borrowed significantly from the Goldsmith Photograph, both quantitatively and qualitatively.” The panel characterized Warhol’s works as “instantly recognizable as depictions or images of the Goldsmith Photograph itself.” While the panel agreed with the Foundation that Goldsmith’s and Warhol’s works “occupy distinct markets,” it concluded that “the Prince Series works pose cognizable harm to Goldsmith’s market to license the Goldsmith Photograph to publications for editorial purposes and to other artists to create derivative works based on the Goldsmith Photograph and similar works.” Hence, the panel concluded that the Warhol works had made unfair use of Goldsmith’s photograph.

Although the panel asserted that its ruling in Goldsmith was “fully consistent” with last year’s Google decision, this assertion is flatly wrong. The Google decision reaffirmed the Campbell test for transformativeness, namely, whether the accused work adds something new and has a different purpose or conveys a new meaning or message. As a matter of law, the Warhol works are unquestionably transformative under this test. The Second Circuit’s “recognizability” test is at odds with Campbell because the Roy Orbison song was instantly recognizable in Campbell’s rap version. The Second Circuit’s insistence in Goldsmith that the second work must have “an entirely distinct [creative] purpose” is inconsistent with Google because Google’s reuse of Oracle declaring code was held to be transformative, even though it served exactly the same purpose as Oracle’s use. This was because the reuse of that code enabled ongoing creativity both by Google and by Java programmers who made apps for the Android platform.

Of course, just because a use is transformative does not automatically mean the use is fair, although transformativeness is generally an important consideration in fair use cases. To me, it matters that Warhol was given the Goldsmith photograph as an artist reference, and nothing in the record indicates that Vanity Fair told him about a one-time-use limitation. The Goldsmith case raises the very tricky question about how to distinguish transformative fair uses from transformative adaptations that infringe the derivative work right. Let’s hope the Supreme Court’s Goldsmith decision provides guidance about how to answer this thorny question.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.

Kluwer IP Law

The 2022 Future Ready Lawyer survey showed that 79% of lawyers think that the importance of legal technology will increase for next year. With Kluwer IP Law you can navigate the increasingly global practice of IP law with specialized, local and cross-border information and tools from every preferred location. Are you, as an IP professional, ready for the future?

Learn how Kluwer IP Law can support you.