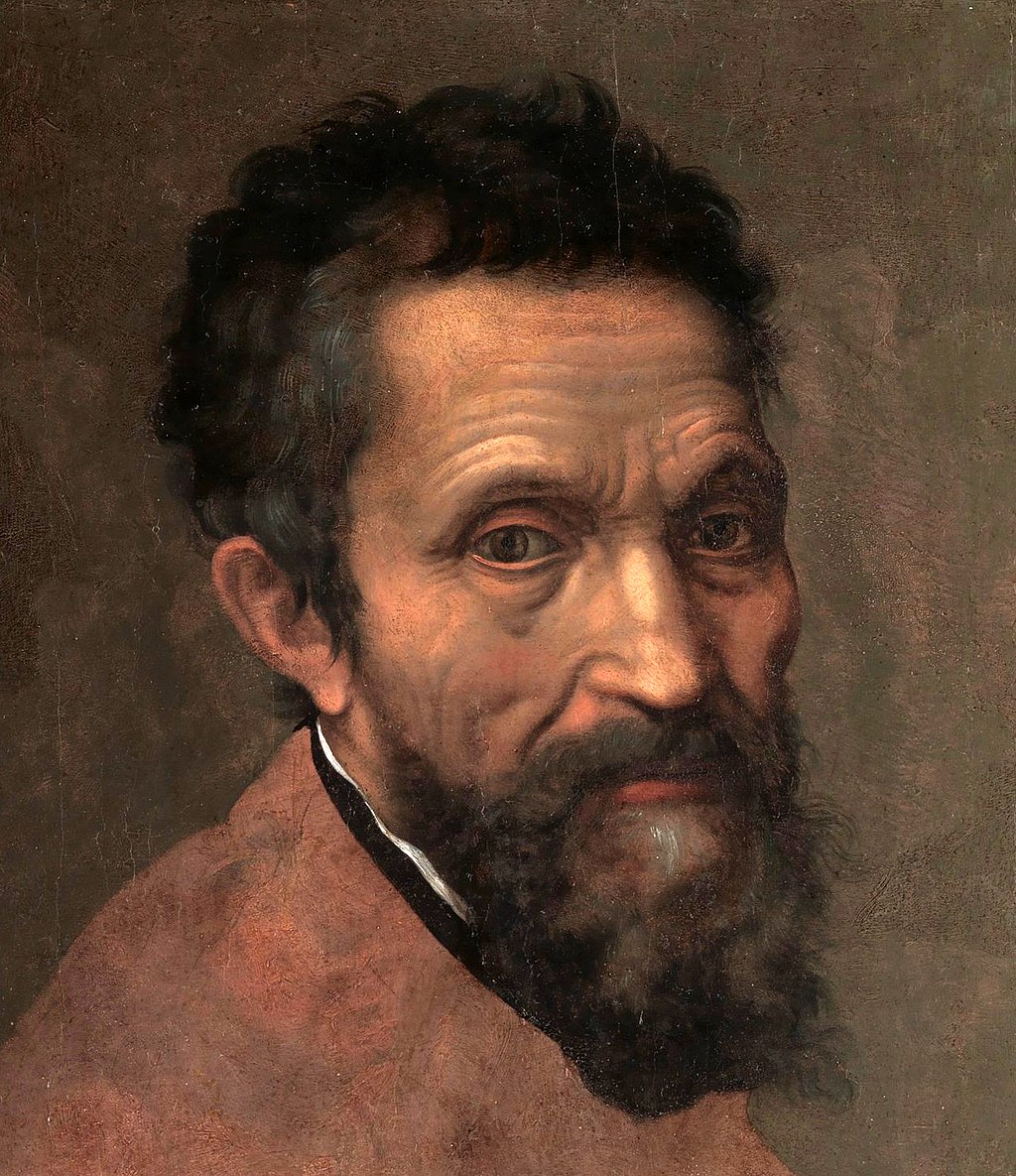

On 20 April 2023, the Italian Civil Court of first instance of Florence (Tribunale civile di Firenze) issued a decision that held unlawful the reproduction by lenticular technique of the image of Michelangelo’s David and its juxtaposition with the image of a male model on the cover of GQ magazine. The reproduction was not authorized by the public museum Gallerie degli Uffizi in Florence where the masterpiece is kept.

The ruling of the Tribunale was as follows:

“unauthorized reproduction of the image of the nation’s State-protected cultural property, in a manner distorting the cultural purpose of the same property, constitutes a civil tort that must be compensated in both pecuniary and non-pecuniary damages”.

The Tribunale di Firenze applied the Italian law: art. 9 of the Constitution, art. 107-108 of the Legislative Decree 42/2004, Cultural Heritage Code “Codice dei Beni Culturali” (the public law on the regulation of cultural heritage) and, by analogy, art. 10 of the Civil Code:

“like the right to the image of the person, specified in article 10 of the Civil code, a right to the image can also be configured with reference to cultural property; this right finds its normative foundation in an express legislative provision, that is, in articles 107 and 108 of the Legislative Decree 42/2004, which constitute norms of direct implementation of article 9 of the Constitution […]”.

The decision mirrors the recent order, in a summary judgment, of the Civil Court of first instance of Venice (Tribunale civile di Venezia) in the Vitruvian Man (Uomo Vitruviano) case commented on by Giulia Dore on this blog.

These recent controversies over the commercial use of images of Michelangelo’s David and Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man emerge from the Italian courts’ decisions while – paradoxically – the reproduction of the image of Botticelli’s Venus for the Italian Ministry of Tourism’s “Open to meraviglia” advertising campaign triggered a controversy about the role of the (Italian) State as custodian of (humanity’s) cultural heritage. In other words, the use of a modified version of The Birth of Venus by Botticelli in the advertising campaign demonstrates that the Italian State, on the one hand purports to decide when the use of cultural heritage is compatible with the “cultural heritage’s scope”, while on the other hand finds it natural to use a controversial modification of a masterpiece like The Birth of Venus to promote tourism.

At the same time, the Italian Ministry of Culture has published new “Guidelines for the determination of the minimum amounts of fees and charges for the concession of use of property handed over to state institutes and places of culture of the Ministry of Culture (Ministerial Decree of April 11, 2023, No. 161)”. These new Guidelines have also triggered a heated debate: some learned societies and scientific associations have raised concerns about the application of the Guidelines to academic publishing. For example, according to the Guidelines, a university press has to pay the Public Sector (Ministry of Culture or public museum) for the reproduction, in a book, of images of public cultural property. As in the Tribunale di Venezia and Tribunale di Firenze’s decisions, the idea is to transform the State into a commercial actor competing with other companies in the market of the commercial reproduction of cultural heritage images.

The decisions of both the Tribunale di Venezia and the Tribunale di Firenze share some conceptual confusion. They merge and overlap pecuniary and non-pecuniary interests, such as public law (Legislative Decree 42/2004) and private law (Civil Code).

This conceptual confusion hides the real interest at stake: the creation of a new form of pseudo-intellectual property (in this case, a pseudo-copyright) that would attribute to the Italian State the power to exclusively control the commercial use of cultural heritage images.

In the Tribunale di Firenze’s decision, while the reference to the constitutional norm seems to represent a mere rhetorical exercise, the content of the exclusive right would be traceable in the provisions of the Cultural Heritage Code. The Tribunale di Firenze focuses attention on the provisions governing the concession of use of the cultural property (art. 106), the instrumental use and reproduction (art. 107) and the concession fees and reproduction fees (art. 108). But these rules say nothing about the exact consistency of exclusivity and especially about its limits in time and breadth. So, the analogical link to civil personality rights would like to allow the introduction in the Italian legal system of a tort (extra-contractual liability) under article 2043 of the Civil Code for violation of an absolute right of the “person” State. The ex post facto judicial creation of an eternal and indefinite pseudo-intellectual property leads to the violation of the principle of the numerus clausus of intellectual property rights.

One of the many paradoxes of this adventurous (and unscrupulous) interpretive judicial operation is the application of the logic of exclusivity to works (cultural heritage) that belong to humanity (and only by historical contingency are in the custody of the Italian State) and were created at a time when neither economic copyrights nor personality rights existed.

The compatibility of this pseudo-intellectual property with the Italian Constitution and European Union law remains doubtful. In particular, under EU law the Italian public cultural property seems to be inconsistent with art. 14 of the CDSM 2019/790 directive on works of visual art in the public domain. In short, the recent Italian cases confirm that the public domain is threatened not only by intellectual property but also by pseudo-intellectual property (an even more threatening surrogate).

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.