Perhaps it comes as no surprise that a copyright dispute regarding a fire-breathing–sneezing dragon would get so heated.

The case of Evans v John Lewis Plc & Anor [2023] EWHC 766 (IPEC) is a copyright infringement claim in which the IPEC (a specialist IP court in the UK) was asked to decide whether John Lewis’s 2019 Christmas advert and an associated book infringed the copyright in a children’s book.

The judgment also offers an insight into how the courts will view a party’s efforts to attract media attention by publicising their proceedings, as John Lewis said was the case here.

Background

Christmas in the UK has become almost synonymous with the arrival of the John Lewis advertisement that for many marks the beginning of the festive season. Since 2009, these advertisements have been created by leading agency, adam&eve.

On 14 November 2019, John Lewis released its annual Christmas advert (the “2019 Advert”). The advert follows Edgar the dragon, who accidentally melts a snowman and burns down a Christmas tree in the town where he lives. It is only when he lights the town’s Christmas pudding and saves Christmas that a predictably wholesome and happy ending is reached.

Within hours of the advert’s release, children’s author Fay Evans (the “claimant”) alleged on social media that the 2019 Advert and an associated book retelling the story (titled Excitable Edgar, “EE”) was unusually similar to a book she had published in 2017 about a dragon that sneezed fire called “Fred the Fire-sneezing Dragon” (“FFD”). This marked the start of a combined legal and publicity campaign by the claimant against John Lewis and adam&eve (the “defendants”).

The Case

Just before Christmas 2020, Ms Evans sent a letter to John Lewis warning it of legal action. John Lewis responded by providing evidence which it said showed that adam&eve had conceived of the idea a year prior to FFD’s publication (the “2016 outline”). It said this showed it had not copied the book. Nevertheless, shortly before Christmas 2021, Ms Evans commenced proceedings against John Lewis and adam&eve alleging copyright infringement. She sought an injunction to prevent the defendants from running the advert and publishing EE, as well as damages and legal costs.

The defendants not only defended the claim, but in light of the publicity that Ms Evans had sought to generate through multiple media campaigns they also brought a counterclaim seeking a positive declaration that they had not infringed the claimant’s copyright, and an order requiring Ms Evans to publicise the judgment if the court ruled against her.

Was Ms Evans’ work protected by copyright?

Ms Evans alleged that artistic and literary copyright subsisted in aspects of Fred’s character and his appearance, and also in ‘narrative elements’ of FFD.

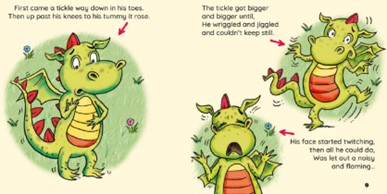

The character traits and appearance features which Ms Evans relied on were that Fred was young, green, accidentally emits fire, is “cute and loveable”, has a ribbed front, triangular spikes on his head, is ‘child-sized’ and has two arms.

These features, and the alleged similarities with John Lewis’s dragon, are shown below in images in the judgment:

Ms Evans also relied on the overarching narratives of both works— a dragon that failed to control its fiery breath, faced criticism and isolation from those around him, before finally gaining acceptance by finding use for his fire. She said these were original and that their inclusion in the 2019 Advert could only be explained by the defendants copying a substantial part of her work.

The judgment does not focus too heavily on the subsistence of copyright. In part, that is because (as we explain further below) by the end of the trial Ms Evans had accepted that the defendants had not seen FFD before creating the 2016 Outline, which removed many of the features which Ms Evans said had been copied. This part of the judgment is nevertheless interesting as it is a good example of the extent to which a fictional character can be protected by copyright. By way of example, Fred’s green colour was not, on its own, said to be protectable. Conversely the judge was satisfied that Fred being ‘child-sized’ was a reflection of the author’s intellectual creation and therefore sufficiently original to be protected. The consideration of the protection of fictional characters was also considered in the UK last year, in the Only Fools and Horses dispute (which we covered here).

Did the defendants copy FFD?

As we mention above, the focus of this dispute is not copyright subsistence, but whether that copyright was infringed.

In the UK, copyright infringement can only occur if there is evidence of actual copying. Given the chronology of events, the case boiled down to one question: did the defendants have access to and copy FFD?

Having heard extensive evidence from those involved in the creative process, and examining documents created throughout that process and the associated metadata, the judge found there was no evidence and that it was extremely unlikely that anyone involved in creating the 2019 Advert or EE had access to FFD. Central to this finding was the fact that the 2019 Advert was the result of an idea which was conceived and first pitched by adam&eve in 2016, before FFD was first made available to the public at its official launch on 7 September 2017. The elements within the 2016 Treatment could therefore not have been copied from FFD.

The 2016 Treatment did evolve throughout 2019, as John Lewis and adam&eve created the 2019 Advert. Consequently, the judge then went on to consider whether the elements of the 2019 Advert and EE which were not also in the 2016 Treatment were copied from FFD. The judge said not. There was an “almost entirely theoretical” possibility that they had done so (because it was available on Amazon and a small number had been sold) but there was “not a scrap” of evidence that the defendants had actually accessed FFD.

On this point, the defendants’ evidence at trial was clearly critical. The judge deemed the creative teams at John Lewis and adam&eve to have been individuals at the top of their game, who were being wholly truthful when they told the court that FFD had not been seen by those involved in the creative process and that, therefore, it had never been mentioned during the creative process.

Ultimately, while there were some similarities between FFD and the 2019 Advert and EE, these were small in number and explained by coincidence and not copying.

Ms Evans’ claim was therefore dismissed.

Key Takeaways

This case, like the recent Ed Sheeran case, confirms that copying by a defendant requires access to the claimant’s work and not just the “possibility of access”. This is important for defendants, who face an increased risk of receiving complaints due to the ease of self-publishing and online availability of various works which they are unaware of.

The defendants in this case were also helped by the fact that they could demonstrate to the court – through solid dated documents and persuasive witnesses – that they had created the 2019 Advert entirely independently. There is really no substitute for good record keeping in those situations.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.

Kluwer IP Law

The 2022 Future Ready Lawyer survey showed that 79% of lawyers think that the importance of legal technology will increase for next year. With Kluwer IP Law you can navigate the increasingly global practice of IP law with specialized, local and cross-border information and tools from every preferred location. Are you, as an IP professional, ready for the future?

Learn how Kluwer IP Law can support you.

It is depressing that we in the UK seem to be acquiring the notion that has taken root in the US that “characters” are protected by copyright. They used to understand perfectly well in the States that it is works, not characters that are protected, but, as the wrongheaded Batmobile case shows, they have lost their way. Let’s not follow them.