The effect of rapid development of generative AI on copyright law continues to challenge the lawmakers and courts. Whilst the UK High Court is yet to reach its decision on liability for copyright infringement in the AI training data in Getty Images v Stability AI, the Chinese case of Ultraman became the first to recognise liability of AI-generated content for copyright infringement.

Unlike the Getty Images case, Ultraman focuses on the liability of the outputs (the AI-generated images), rather than the inputs (AI training data). Nonetheless, this case is a welcome addition to the emerging case law on AI and copyright around the world.

Given the reduced damages awarded by the Guangzhou Internet Court and the reasoning behind the decision, AI’s strategic importance is at the core of the Ultraman decision. The court made clear its intentions not to overregulate AI service providers.

Background

The case was brought by Shanghai Character License Administrative Co. Ltd – licensee of Tsuburaya Productions Co. Ltd, who is the Japanese owner of the copyright in Ultraman. Ultraman is a Japanese science fiction media franchise, which began with the television series in 1966 and later became internationally well-known. In 2013, the Ultraman series was certified by the Guinness World Records as the “TV Program with the Most Spin-Off Series”. In China, the franchise could be said to enjoy some form of a cult status, winning numerous awards and dominating toy sales (you can read more about Ultraman’s awards on the first pages of the Ultraman judgment).

The claimant had an exclusive licence in Ultraman in China, including right to pursue copyright infringement in court.

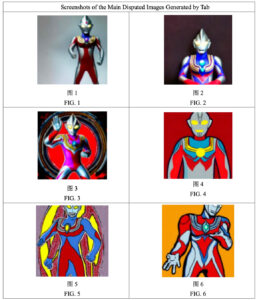

The defendant (an undisclosed AI company) operated a website named “Tab” (alias), which was effectively a chat-bot capable of generating AI images at its users’ request. When asked to generate an Ultraman-related image, Tab generated an image argued to be substantially similar to the claimant’s licensed Ultraman.

In its original claim, the claimant alleged that the defendant used the claimant’s copyright protected works to train its AI models, to generate substantially similar images. Importantly, the disputed images were provided by a third-party service provider and not the defendant directly.

The claimant later amended its claim to copyright infringement, arguing infringement of reproduction, adaptation and information network dissemination rights (the last is similar to communication to the public in the UK and the EU). The claimant requested an order that the defendant:

- Immediately stopped generation of the infringing Ultraman images and deleted the disputed images from its training dataset;

- Paid damages for economic loss and reasonable expenses in the amount of RMB 300,000 (around 38,000 EURO or 32,000 GBP); and

- Bore all costs of these proceedings.

Although the defendant took immediate steps to remove the contested images from its website and to introduce the keyword blocking measures (blocking “Ultraman” and keywords containing “Ultraman”) as soon as the case documents were served, this was not enough. In particular, it was noted that users could still generate Ultraman-related images if the request contained other Ultraman-related search terms, such as “Tiga” without the word “Ultraman”. Tiga is one of the fictional characters in the series.

Notably, the Tab website did not contain any relevant user agreement or terms of service that would inform its users of third-party rights that may be present in the AI-generated materials.

Reasoning

In reaching its decision, the court needed to answer two questions:

- Whether the defendant had infringed the claimant’s copyright (in particular, rights of reproduction, adaptation and information network dissemination); and

- If so, what liability should the defendant incur?

Having conducted its analysis of the law and facts, the court answered affirmatively to the first question. The court established that Ultraman was an original work and, therefore, protected by copyright. Considering the high popularity of the series in China, the court found that the defendant could have had access to the original images. Full or partial reproduction of the original images by the Tab website, therefore, infringed the claimant’s reproduction right. Considering that the generated image contained a combination of the original character and added new features, the claimant’s adaptation right was also infringed. The court also found an infringement of the right of dissemination via information networks. In doing so, it relied on its analysis with regard to the rights of reproduction and adaptation.

On the question of liability, the court referred to the Chinese AI law – the Interim Measures for the Administration of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services, implemented on 15 August 2023 (the “Interim Measures”).

According to the Interim Measures, the defendant fell within the definition of an AI service provider and, therefore, was required to “take measures, such as stopping generation, stopping transmission or eliminating the illegal content, make rectification through measures such as model-based optimisation training, and report findings to the relevant competent department”, which the defendant did not do.

The court rejected the defendant’s argument, that the third-party provider was ultimately responsible for providing the disputed images. Having identified the defendant as the AI service provider, the court found that the defendant had failed to fulfil its duties as a service provider. As such, the defendant’s website fell short of the following requirements introduced by the Interim Measures:

- Complaint and reporting mechanism. The defendant did not make it easy for the rights holders to complain about the infringement of their IP rights.

- Potential risk notifications. Generative AI service providers are obliged to notify users of potential risks, including that the users are prohibited from using the services to infringe upon third parties’ IP rights, which the defendant did not do.

- Labelling of generated content. The defendant should have labelled Tab’s content as AI-generated, so that such content is not misidentified by the public as the original images that belong to the rightsholder.

Although the defendant adopted keyword filters to prevent AI from generating images of Ultraman, these measures were not entirely effective. The claimant demonstrated at trial that similar content could still be generated when related keywords were entered by the users. Therefore, the defendant failed to implement preventative measures that would be effective enough to completely stop all generation of disputed images.

Even though the claimant also pleaded for the deletion of “the disputed Ultraman materials from [the defendant’s] training dataset”, the court did not make such order. This is because the defendant sourced those images from an unrelated third-party service provider.

Although the judge ultimately sided with the claimant in finding copyright infringement, the court awarded damages of only RMB 10,000 (around 1,270 EURO or 1,070 GBP) instead of RMB 300,000 (around 38,000 EURO or 32,000 GBP). In calculating this award, the court took into account the following circumstances of the case:

- The significant market visibility of Ultraman;

- That in response to the claim, the defendant has actively adopted technological measures to prevent continued generation of the disputed images (albeit with only partial success);

- That the defendant only provided the disputed images to its paid members, which means the infringement had limited reach;

- That the claimant incurred losses when collecting evidence of infringement and protecting its rights.

Order

The court ordered that:

- The defendant was to cease any infringement of the claimant’s copyright;

- The defendant was to compensate the claimant in the amount of RMB 10,000 (around 1,270 EURO or 1,070 GBP); and

- All other claims of the claimant were rejected.

Implications

Although the full implications of the Ultraman decision are yet to be seen, we can already draw certain inferences and see the direction that the Chinese courts are likely to take when it comes to generative AI.

Having reached its decision in record time (just under one month since the case was filed), the Guangzhou Internet Court emphasized the strategic importance of AI for future technological advancements. It stated that “since the generative AI industry is still at its early stage of development, it is unwise to overburden service providers with their duties”. Importantly, the court noted that “in the process of rapid technological development, service providers should actively take reasonable and affordable precautions”.

The decision in Ultraman shows the difficulties that courts are beginning to face when it comes to reconciling AI regulation and the need for continued technological development.

The Interim Measures are, effectively, the Chinese analogue of the EU AI Act (while the UK is taking a very light-touch regulatory approach so far). Guangzhou Internet Court was a real-life test of the Interim Measures. The Ultraman decision is China’s first ruling on liability of companies specialising in generative AI. Although the case took place in China, it is a lesson to AI service providers all over the world. It raised interesting issues around liability of AI service providers and their duty of care to the public and the copyright holders. It is a warning for AI service providers to be ready for claims if they fail to satisfy the terms of the relevant AI regulations.

Overall, the judgment considers the claimant’s IP rights, as well as the burden placed on the defendant when it comes to enforcing those rights. Whether the rest of the world will follow along the same lines as the Guangzhou Internet Court, only time will tell.

NB: in preparing this analysis the author relied on the English translation of the decision produced by Jiaying Zhang and Yuquian Wang under the supervision of Prof. Robert Brauneis of the George Washington University Centre for Law and Technology. Full text of the translated decision is available here.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.