Introduction

The current international legal framework for text and data mining (TDM) is highly disharmonized, showing a variety of approaches that span from completely unregulated to partially and fully regulated. Furthermore, regulation is not uniform, and it addresses relevant stakeholders (creative and content industries, tech firms, users, research, and the public sector) in various ways. In this fragmented landscape, self-regulation (e.g., contracts) may play a decisive role in the final allocation of rights and obligations. We are interested in exploring whether in the EU Arts 3 and 4 of the Copyright in the Digital Single Market Directive (CDSMD) played a role in shaping the contractual practices in selected industry sectors in relation to the licensing of works as training data.

Globally, the scope of what is encompassed under TDM techniques may vary according to domestic legal definitions. Nevertheless, part of the literature has claimed that mining copyrighted works for purposes of TDM does not involve expressive uses, and, therefore, should not raise any copyright issues (see, e.g., here and here). Despite similar normative claims, the legal uncertainty connected to the fact that “[e]ach stage of a TDM project is potentially constrained by copyright depending on how the scope of protection is interpreted”, has led to a significant number of changes in copyright laws across the globe to accommodate text and data mining within a clearer framing (see here and here).

Under EU Law, the most significant developments were introduced by articles 3 and 4 CDSMD, and its national implementations. While art. 3 is purpose-limited to scientific research and is imperative (art. 7(1), CDSM), art. 4 allows more broadly acts of TDM when the “use of works and other subject matter […] has not been expressly reserved by their rightsholder in an appropriate manner” (art. 4(3), CDSM).

Methodology

We selected representative industries for art. 3 and art. 4 CDSMD and analyzed the publicly available documents that may regulate the use of content for TDM. If TDM was not mentioned we accepted other terms, such as machine learning and/or artificial intelligence purposes and we flagged this accordingly. We selected the Scientific Publishing industry to better understand how the obligations under art. 3 are being dealt with by this industry, considering its centrality to the conceptualization of the provision (see e.g., the impact assessment of the CDSMD). For art. 4 CDSMD, we decided to investigate Stock Images providers for two main reasons: the recent litigation started in the US and UK promoted by a large stock images platform, and the fact that some of these companies already provide commercial options for training purposes.

There are numerous commercial Scientific Publishers and Stock Images providers. To work with a feasible sample, we limited our research to 10 Publishers and 13 Stock Images Providers. To identify the most representative Scientific Publishers, we relied on a recent study that mapped “the 100 largest scientific publishers by journal count”. For the Stock Images providers, we used Google Trends and Google Search tools to identify the first results and the most searched companies and websites worldwide related to the term “stock images” for the last 12 months.

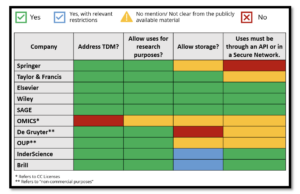

Scientific Publishers

Analyzing Commercial Scientific Publishers, we found indicative evidence of a higher awareness about TDM than with the Stock Images providers. This awareness is manifested by either directly addressing TDM in their Terms of Use or Content License Agreements, or alternatively by having specific policies, FAQs or summaries for TDM. 7 out of 10 publishers allow TDM only for non-commercial scientific/academic research (e.g., Springer, SAGE, Wiley and Elsevier). This is not exactly the wording of the CDSMD, which speaks of research purposes by research organizations, cultural heritage institutions and other selected entities. As it can be noted from the CDSMD Impact Assessment, this was a deliberate choice: the adopted option 3 covers “text and data mining for the purposes of both non-commercial and commercial scientific research”. Some publishers seem to have adhered to a slightly different wording. To the extent that this wording limits Art. 3 it should be considered contractually void and unenforceable.

There also seems to be a lack of clarity about which uses are allowed under the licenses. Some providers formally allow TDM but at the same time prohibit or limit the use of automated tools (see, e.g., Elsevier) and/or certain uses that may be crucial for the reproducibility and verifiability of the research results, as is the case of De Gruyter Group. The latter, in its general license, provides that “[t]he Contents are only made available via De Gruyter Online. Archiving of the Contents (in whole or in parts) requires prior written approval from De Gruyter”. Whereas this could be seen as a potential restriction to the storage rights provided in art. 3(2) CDSM, the text of item 7.8 of the License states that “[a]ny mandatory rights of use of the client under statutory provisions remain unaffected”. Although not an uncommon solution in contract drafting, this provision does not help to bring clarity in a crucial area such as scientific research.

Finally, we also found that in several occurrences, the uses for research purposes must be carried out within a controlled environment, either a Secure Network (e.g., Inderscience and Brill) or through the provider’s API(s) (e.g., Elsevier, Wiley and SAGE). The Secure Network is mostly addressed as a secure online environment with access control, usually provided by the Client/Licensee of the Publishers (e.g. University), which may be associated to the provisions on security and integrity contained in art. 3(3), CDSMD. On the other hand, the mandatory use of APIs may require additional investigation. While some companies publicly state that the use of APIs is required for security reasons, it was not possible to actually use and test the APIs to ensure that there were no restrictions to the users’ rights contained in art. 3. Should the use of APIs become a way to reduce the scope of Art. 3, for instance, in relation to the type of uses, type/number of searches or other expressions of scientific research, APIs should be seen as a limitation of Art. 3 not covered by the exemption for integrity measures. There seems to exist an enduring and unaddressed grey area between what is a legitimate integrity and security measure and what is an access control tool intended to circumvent the fundamental – and imperative – rights of Art. 3. The need of researchers to access large scientific databases, and thus to accept the conditions that lead to this access, plays a role in what becomes an acceptable practice.

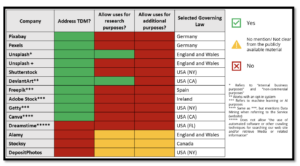

Stock Images’ Providers

From the analysis of the publicly available documentation on the Stock Images providers’ websites, we found that most of them (9 out of 13) address data mining, even though Freepik, Adobe Stock, Getty and Canva employ terms like machine learning or more generally refer to uses for “artificial intelligence purposes”, sometimes without offering a proper definition. We observed that most of the providers that address TDM or uses for AI/ML purposes expressly prohibit such practices. Even though some of these documents make it clear that the selected governing law is one that would authorize TDM for research purposes as a copyright exception (e.g. Germany), these prohibitions are usually expressed in the documentation regardless of the intended purposes. This leads to a scenario where many of these provisions will be considered void for the parts that do not allow Art. 3 uses. For the few providers that allowed TDM, the practice was either limited to the use of an API and for limited purposes (Unsplash), or via opt-in (DeviantArt).

Some of these providers are known for licensing the use of images for free and have permissive licenses allowing the user to download, copy and modify the content for both commercial and non-commercial purposes (e.g. Pexels and Pixabay). As provided in Pexels’ Term and Conditions (Section 5.5.), the company grants the user a “license to download, copy, modify, distribute, perform, and otherwise use the Content … including for commercial purposes” (emphasis added). Even though the user is allowed to copy, download and “otherwise use” the Content, Section 6.1 of the same document requires that the users “will NOT: […] use the Service for the purposes of data mining, extraction, scraping and/or the use of programs or robots for automatic data collection and/or extraction of digital data from the Service and/or the content made available thereon, whether for machine learning purposes or otherwise”. In what could be understood as an apparent contradiction, these provisions grant the user a set of rights needed for data mining but require the user not to exercise such rights for TDM and AI purposes. This is an interesting aspect since TDM and AI (generally treated together) are arguably offered more restrictive conditions than those granted to human agents.

Finally, restrictions to TDM and uses for ML/AI purposes appear both in the basic free options as well as in cases when the providers make premium/paid subscriptions available. For example, Unsplash offers a regular “Unsplash” License and the “Unsplash +” License with additional features. Even though the Unsplash + Terms and License grant to the user the rights to “download, copy, modify, distribute, perform, and use Unsplash+ photos […], including for commercial purposes”, they expressly prohibit “using Unsplash+ photos […] for machine learning, AI, or biometric tracking technology.”

Conclusion

The commercial scientific publishing sector shows a great deal of familiarity with the issue of TDM and the conditions of Art. 3 CDSMD. However, they seem to have adopted a position arguably more restrictive than that allowed by the law, i.e., excluding commercial research when performed by research organizations, cultural heritage institutions and other qualifying entities for research purposes. Whereas the unlawfulness of this restriction is unquestionable, it would be interesting to understand the reason for that. It could, of course, simply constitute an excess of legal caution leading to a partially unenforceable contractual condition. Or perhaps it could point towards a precise business strategy that conditions the availability of certain content (an availability that could be withdrawn) to the acceptance of terms that are at least in part unlawful and which are enforced via APIs.

Moving to the stock images sector, it is interesting to observe cases where content is licensed liberally for most uses, except for TDM/AI. There may be several explanations for this approach, from caution to uncertainty, given the sudden rise of generative AI applications and the connected concerns about the effect that it could have on the creative process, as exemplified by some of the court cases recently started by artist or stock images providers against AI developers.

In both instances, further attention should be given to the use of APIs to control access and regulate the use of content. APIs are standard forms of access content, and their usefulness and even essentiality in certain conditions is out of question. However, APIs, within Arts 3 must represent and be devised as technical solutions to problems like integrity and security of databases and networks. Should they assume other, less neutral, roles such as restricting the type of uses that Art. 3 reserves imperatively to researchers, then APIs will logically stop being an allowed integrity measure and become an unlawful Art. 3 restriction.

Finally, there is the confusing use of terms like TDM, AI and machine learning as interchangeable and undefined expressions. Their relationship is not fully clear in the law, but this does not mean that contractual practice should perpetuate the same ambiguity. The recent lawsuits debating the use of copyrighted works for training generative AI systems just reinforce the need for better clarity in the relationship between TDM, especially for research purposes, and the fundamentally different (but technologically akin) generative AI.

Copyright theory suggests that extracting information, patterns and correlations from large sets of copyrighted works should not be subject to the authorization of right holders. Statutory solutions that conditions these uses to authorizations should be drafted and interpreted cognizant of the fundamental rights implications of this policy choice. Conversely, the use of works for training an AI system that generate outputs able to compete or even to fully replace the works used for training is an entirely different activity which may very well fall in the exclusivity and control of right holders. Within this second framing, i.e., generative AI, Art. 3 and especially the opt-out of Art. 4 acquire an entirely new and rather interesting potential. Research, however, should not pay the price of legal and contractual ambiguity.

The links provided in this article reflected the content referred to at the time of its writing (July 2023). The documents used in this research are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LOL29A. In addition, this study focused on the wording adopted in the licenses and related documents and not on their interpretation or application in a specific jurisdiction. Our main interest, at this point, was to compare the wording adopted by the industry players in their public documents and those employed in the CDSM.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.