Part 1 of this post explained the background to the development of shadow libraries and their growth in recent years. This post will analyse the nature of the works downloaded and discuss the implications of shadow libraries for the future of scholarly publishing.

What is being downloaded?

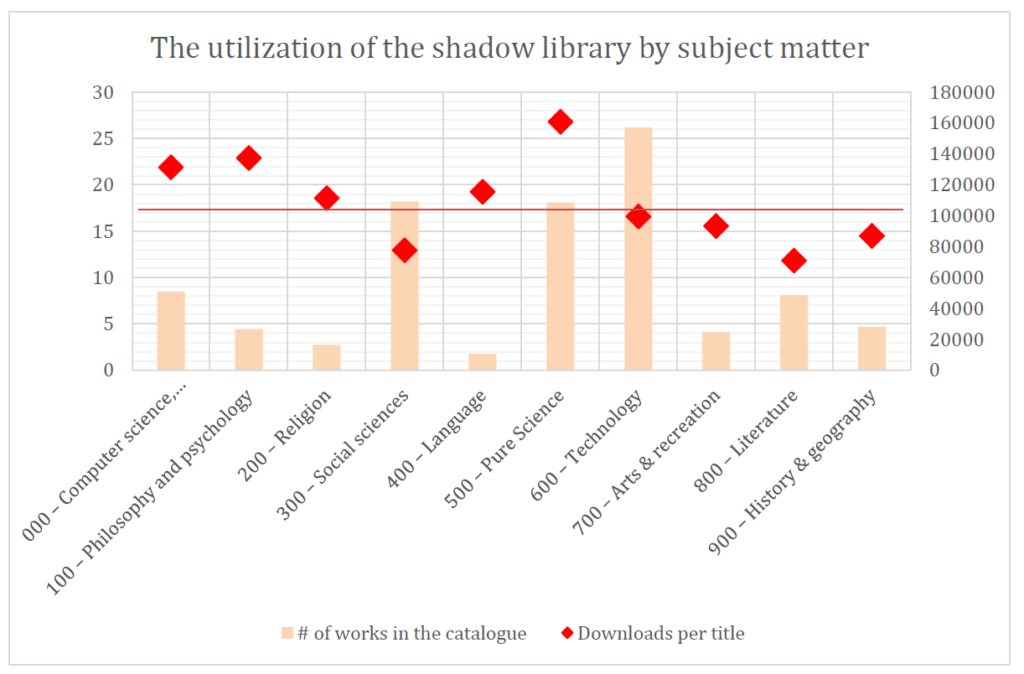

Over the 4.5 month period in 2014/15, 760,868 different documents were downloaded for more than 16 million times. As can be seen from Figure 4, neither the supply, nor the demand of books is uniformly distributed.

Figure 4: The utilization of the shadow library by subject matter

Figure 4: The utilization of the shadow library by subject matter

In the graph, the bars represent the number of unique titles in the catalogue by Dewey topic category. Almost half of the titles in the catalogue do not have a Dewey classification; these are mostly older works and/or were published in Russia/Soviet Union. Most of the rest of the catalogue belongs to the Technology domain (~157k works), Science (~108k), and Social Sciences (~107k). On average, a title was downloaded 17 times (the horizontal red line), with science and computer science works enjoying higher than average download figures, and social sciences and literature experiencing below average demand (red diamonds, left axis).

The list of the 20 most downloaded books in Table 2 reflects these general trends, and also sheds light on the complex nature of piratical demand. The list is (almost predictably) led by sex, closely followed by the popular sci-fi of the day. But it also reflects the needs of an international community (English grammar), and the scientific zeitgeist (postcolonial studies, feminist thought, and machine learning).

Table 2: Most downloaded books

Table 2: Most downloaded books

If we start to disaggregate these general trends, we find an incredibly complex world, where individual countries show significant differences in both what they read the most and on which scientific domain they focus. Different countries have very different “information diet” profiles, i.e. which top level Dewey topic domain dominates their overall consumption. For example, hard sciences represent more than 20% of the total downloads of Japan, China, and Columbia, but less than 5% of Kuwait, Qatar, Zimbabwe, or Uganda, countries which, on the other hand, consumed way above average numbers of titles from the social sciences and technology domains.

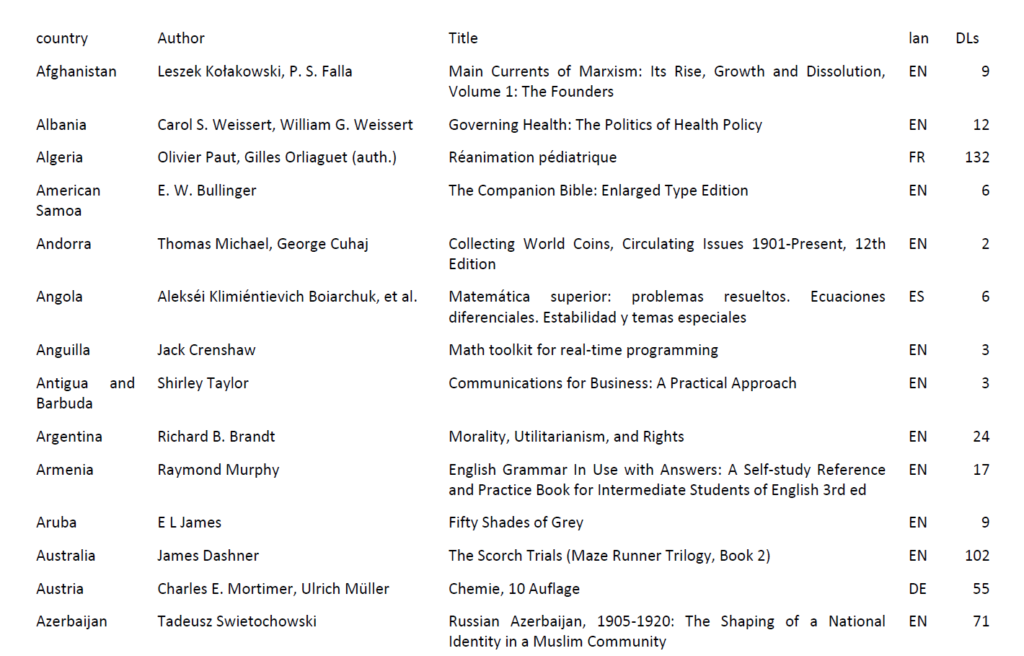

Table 3 below lists the most popular work in each country (the full table is available by clicking on the image). The most popular book in Iran was on Fish processing technologies, in China on Quantum Mechanics, in the USA on Black Feminist Thought, in India on quantitative aptitude test solutions, in Egypt on electronics, in the Netherlands on economics, in Greece on European history, in Algeria on paediatrics, in Vietnam on French Grammar, in Spain on English Grammar, in Iraq on Obstetrics, in Indonesia on Research design, and in North Korea on Linux network programming.

Table 3: The most popular work in each country (click on image for full table)

Table 3: The most popular work in each country (click on image for full table)

These country level characteristics reflect the complex drivers of shadow library use: the global trends in scientific discourse, the structure of, and the money spent on public tertiary education, the labour markets in local economies, wealth, and the privilege of access, the quality of library system, the price and electronic availability of individual works, the diversity of local user communities, etc. Scholarly piracy is driven by the complexity of these local contexts, and shadow libraries’ ability to serve them all. This also means that as long as legal alternatives are not able to address, equally well, all these different challenges, the incentives that drive the growth and use of shadow libraries will remain.

Implications

What kind of impact could shadow libraries have on the current system of scholarly publishing? The review of the music and audiovisual industries’ last two decades of fighting online piracy may help us answer this question. The entertainment industries spent two futile decades trying to find first technological, and later legal solutions to the piracy of their products. DRM and copy protection technologies did not work, and neither did the lawsuits against their customers. File sharing technologies rapidly evolved to eliminate all potential technical points of control, and decentralized themselves beyond reach. The Pirate Bay is still up and running, despite countless lawsuits, imprisoned founders, and EU-wide blocking injunctions.

In light of their course of action, it seems that the scholarly publishing industry understands that it is close to impossible to efficiently fight scholarly piracy. Gigapedia, the predecessor of LibGen, was relatively easy to shut down, as it relied on a centralized database, and a centralized document repository. LibGen and SciHub are much more difficult to eliminate, as they are both radically decentralized, and already exist in multiple copies all over the internet. This might also explain why there is only one court case against these services. A New York court issued an injunction against both sites, forfeited their domain names and ordered damages against the administrators, but none of these measures had any practical effect. In the case of journal articles, publishers have demanded that academic libraries focus more of their resources on enforcement, but this only had a limited effect, if any, on the outflow of materials. As it stands now, academic piracy seems to be unstoppable.

Under these conditions, academic publishers had to ask themselves if the copyright and exclusivity based business models are sustainable. For a number of reasons, the answer might still be in the affirmative. Both the US and the EU have mandated open access publishing for publicly funded research, creating a lucrative revenue stream for publishers in the form of article processing fees which are not threatened by piracy. The fact that the scholarly pirates (the scholars themselves) are not the ones paying for the materials (those paying are the academic institutions, libraries, and in some cases government agencies) may ultimately mitigate the negative effects of piracy, where illegal consumption substitutes sales. One illegally downloaded scholarly monograph, already priced for the library market, does not diminish sales to individuals, but may generate a purchase by the library at the request of the researcher who obtained a free sample copy through the shadow library.

The most important impact of music and audiovisual piracy was that it forced businesses to innovate and mitigate the negative impact of mass infringement. This process ultimately produced the flat-rate “all-you-can-eat” subscription services, which grew to dominate the online music and movie markets. It is not clear to what extent one can attribute the recent increased willingness of university libraries, and institutional consortia to let their journal licensing agreements with Elsevier lapse to the easy availability of the same corpus via alternative, often not-so-legal means. No library official will acknowledge that they hope that their students and faculty will fill their access gaps with SciHub. In any case, there is a growing institutional ecosystem of access, which includes radical alternatives, like shadow libraries, personal, preprint, institutional archives, as well as green and gold open access repositories. Even if publishers could curb one component, the shadow libraries, they cannot control all the free and open access alternatives.

This slow erosion of the control over access may explain the shift of academic publishers towards data-centred business models. Over the last few decades academia has undergone a substantial degree of quantification, where not just citations, but all other aspects of scholarly work have became measurable and consequently thoroughly measured. Almost all major publishers have recognised the potential of this data-based market and invested heavily in software and services which facilitate the circulation of materials related to scholarly work, and generate data on this circulation. These tools do not require paywalled content. In fact, they all thrive in environments where there are no artificial technical or legal boundaries to the accessibility, circulation and consumption of content.

Based on the data, shadow libraries facilitate a knowledge transfer on a scale unseen since the widespread piracy of the French Encyclopaedia in the 18th century. They also serve as probes into the complex system of interlocking crises which transcend academic publishing, and the production, circulation and use of scientific knowledge across the globe. They may also be seen as bellwethers of impending change. The current de facto radical open access may ultimately force the development of an equally radical, but ultimately legal open access regime. But no such change comes without a cost. The publishing industry has already moved on to the next lucrative market. The academic community must make sure that the knowledge it generates about itself does not get privatized in the same way as its scholarly output was privatized before.

Acknowledgments

The research received funding from the H2020 Research grant “OPENing UP new methods, indicators and tools for peer review, dissemination of research results, and impact measurement”, and was carried out on the Dutch national e-infrastructure with the support of SURF Cooperative.

For further details of the sources mentioned in this post, and other related reading, please see here.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.