The first post of this two-part series on Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) discussed the copyright implications of the use of different online services in the context of ERT. The second part explores the data protection (DP) issues. Our analysis evaluates compliance of platforms with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), in order to assess how the shift from face-to-face to a digital teaching dimension affects teachers’ and students’ privacy in universities.

The first post of this two-part series on Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) discussed the copyright implications of the use of different online services in the context of ERT. The second part explores the data protection (DP) issues. Our analysis evaluates compliance of platforms with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), in order to assess how the shift from face-to-face to a digital teaching dimension affects teachers’ and students’ privacy in universities.

ERT requires the collection and processing of different types of personal data – including in some cases sensitive data – from both teachers and students. When based in the EU or offering services to subjects in the EU, ERT service providers must adhere to the rules of the GDPR. The latter provides a framework for the protection of individuals (“data subjects”) with regard to the processing of their personal data, and for the free movement of such data. It empowers data subjects to control information relating to them (Arts. 12-22 GDPR) and clearly articulates the standards of accountability for actors involved in the processing.

Setting the scene: applying data protection rules in ERT

The first step in establishing the framework for our analysis is to identify the purpose, i.e. the reason why personal data is used, and the legal basis the data controller relies on for the processing of that data. In ERT, personal data of students and teachers is processed for the institutional purposes of a university, i.e., to provide education (e.g. deliver lectures, provide room for discussion, make assessments). To achieve this purpose, the lawful basis would appear to be the necessity to perform either a task in the public interest (art. 6(1)(e) GDPR) or a contract to which the data subject is party (art. 6(1)(b) GDPR).

Second, it is crucial to articulate the rights and responsibilities of the actors involved in the processing. In an ERT scenario, the university is, in principle, the data controller that processes the data of its students and teachers (data subjects) for institutional purposes. The data controller is the person or entity which determines the purposes and the means of the processing of data (Art. 24 GDPR). She shall ensure compliance with the GDPR and apply DP principles (see Art. 5 GDPR) in the processing.

When services used for ERT are managed entirely within the university (including data storage, etc.) the compliance responsibility remains with the institution. However, when universities partially or entirely outsource the processing of data to an external service, the latter will assume the role of data processor (Art. 4(1)(8) GDPR). In appointing the processor, universities must ensure that the external provider offers appropriate safeguards for the protection of data and, in general, guarantees GDPR compliance. In this respect, it must be stressed that if the ERT platform processes personal data for purposes other than those relating to education (such as advertising or the improvement of the service), depending on the circumstances, the university could become joint controller of those processing operations (CJEU, C-40/17, Fashion ID).

When teachers process student data for educational purposes, they act as persons authorised to fulfil the task of the controller. To this end, the university is obliged to clearly instruct them (see Art. 29 GDPR). However, this scenario has been challenged by the COVID-19 outbreak. Lacking sufficient (or any) instruction by universities and often at their own cost, many teachers had to act autonomously to ensure delivery of ERT. In doing so, they became, although probably unaware, controllers. They determined the means (service) and the purpose of the processing of student data.

Coming to Terms with data protection

Our analysis focuses on three major DP aspects common to all terms of the services examined:

1) the purpose pursued by the service;

2) the lawfulness of the processing;

3) the data subjects’ rights.

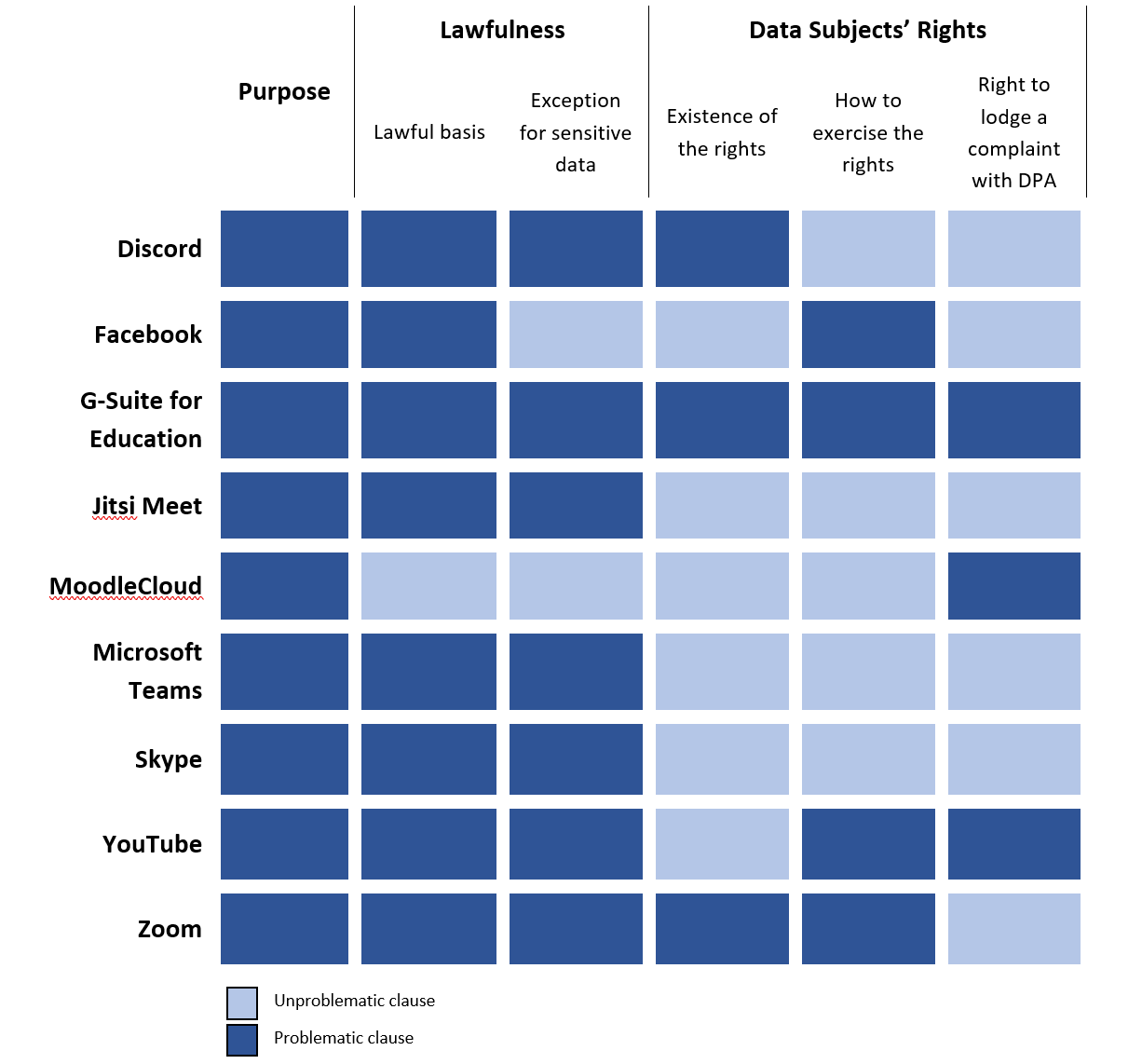

According to Arts 13 and 14 GDPR, all relevant information about these aspects must be provided in a clear and understandable way to the data subject. Such mandated disclosures are conditio sine qua non to understand the core activities performed on data. Our findings are summarised in the table below, with problematic aspects highlighted in a darker colour. The conditions of flagging each provision are explained in the following sections.

Purpose of the processing

“Generalistic services”, such as Facebook and YouTube, are not specifically designed to serve as data processors in an ERT context, while other services such as Moodle and GSuite are tailored for educational uses. The latter explicitly mention in their terms the possibility of being appointed as processors. Nevertheless, all the services analysed also pursue autonomous purposes, which should constitute an essential factor in a university’s choice of ERT provider. For instance, as underlined by the Italian Data Protection Authority, data processed on behalf of universities (and schools) must be used only for the purpose of remote teaching.

Further uses by the service provider are not unlawful a priori, but they must rely on a suitable legal basis and ensure the information obligations towards the data subjects are fulfilled. However, our analysis shows that the purpose of the processing is not always transparently described. For example, some services (YouTube, Skype, Zoom, GSuite) provide a detailed list of categories of data processed and a list of purposes, but it remains unclear which data corresponds to each purpose. Sometimes, the correlation between data and purpose is perfectly illustrated, but the description of the purpose itself is cryptic (e.g. in Moodle, one purpose is verbatim “User code repository”). In other cases, the description of the purpose is too vague: e.g. Jitsi and GSuite refer to the very general clause of the “improvement of the service”.

Lawfulness of the processing

To be lawful, the processing must be based on one of the conditions of Art. 6 GDPR. Most of the services do not provide sufficient and clear information: in some cases, it is hard to identify which data is processed for a particular legal basis (Discord, GSuite); in others, the link between the purpose and the corresponding legal basis is not clear (YouTube).

When the legal basis for processing is consent, further problems arise. Discord mentions the possibility of ‘implied’ consent, and Moodle stipulates that agreement to the terms constitutes ‘explicit’ consent. Both provisions are problematic: the first because the GDPR requires consent to consist of a clear affirmative action; the second because it constitutes bundle consent, where it is impossible for data subjects to give a separate consent to each use. Meanwhile, Zoom provides that when the user (such as a teacher) records a meeting, students can either accept the processing of their data or leave the meeting. In this case, consent is unlikely to be freely given (see, EDPB Guidelines 05/2020).

Another problematic lawful basis is the legitimate interest of the controller or third party. Often only vaguely described (Facebook, Zoom), the use of this legal basis requires a balancing test between the legitimate interest of the controller or third parties on the one hand, and the interests of the data subjects on the other. The process and outcome of such balancing is not disclosed in any of the privacy policies, as there is no formal obligation to do so. However, if the university is found to facilitate or enable in some form further processing, it remains unable to evaluate or affect the DP measures taken by the other controller.

Finally, many ERT providers collect sensitive data. For instance, when an online tool allows video recording, it is likely to capture one of Art. 9 GDPR particular categories of data (e.g. if a student wears a hijab, this potentially shows her religious beliefs). Therefore, when the service processes such data for its own purpose, it should specify on which lawful condition it is relying (Art. 9(2) GDPR). Apart from Moodle and Facebook, such conditions are not mentioned in the privacy policies analysed.

Data subjects’ rights

A common thread among the Terms is the systematic reference to the full list of data subjects’ rights (except GSuite). Nevertheless, the existence of such rights is sometimes accompanied by vague formulas like “you might” or “may have the right to”. This is the case for Discord and Zoom. Microsoft Teams formally complies with the information obligations about data subjects’ rights, but the reader needs to navigate a combination of policies. In other cases (Zoom), it is not even clear which privacy policy among the two accessible on the website governs the processing (see here).

Most policies include an explanation for data subjects on how they can exercise their rights (usually through the personal settings or by contacting the Data Protection Officer via email). Nevertheless, some rights remain orphan (e.g. in Facebook and YouTube it is not clear how to exercise the right to restrict the processing).

In any case, we argue that providing a pro forma mention of compliance with data subjects’ rights does not serve the purpose of empowering concerned individuals so that they can make full use of the GDPR toolbox (see also here). Indeed, when the information is insufficient or not clear, it is hard for the data subject to act upon.

Finally, most services recognise and properly inform data subjects about the right to complain to a supervisory authority. Nevertheless, our analysis identifies a few problematic formulations. For instance, Moodle recognises the right to lodge a complaint with a Data Protection Authority (DPA), then adds the contact details of the Irish DPA. This might lead the data subject to think she is only entitled to file a complaint with that specific DPA. YouTube affirms that “you can contact your local DPA if you have concerns regarding your rights under local law”, somehow altering the actual scope of Art. 77 GDPR.

Conclusions on data protection

ERT raises significant data protection concerns. In this post, we have focused on three controversial points. First and foremost, the significance of the choice of a reliable service provider cannot be stressed too much. Since the emergency situation often forced the university to outsource the processing for ERT, it bears the obligation of choosing an appropriate data processor and avoiding reliance on providers that pursue autonomous goals depending on their business model (e.g. advertising). In addition, the choice of ERT provider should not force students and teachers to be subject to data collection and further processing for purposes that are not related to the provision of education or other institutional goals of the university. Universities should evaluate their position in relation to the platform’s processing for autonomous purposes, considering the hypothesis that in some cases they could be qualified as joint controllers for such processing operations. They should then provide complete and clear information to students and teachers about the ERT processing as a whole, clarifying who is responsible for what and explaining what the data subject can do if something goes wrong. On a more general note, the preliminary results of our study show a worrisome trend towards the systematic violation of the principle of transparency. It is often unclear which data is processed, the purpose for which it is processed, and according to which lawful basis (a trend confirmed here). On the contrary, data subjects’ rights are usually acknowledged. Nonetheless, it is doubtful whether a data subject can exercise her right effectively when substantial information remains opaque. The lack of oversight through the overarching principle of transparency considerably affects the exercise of data subjects’ rights, thus raising compatibility concerns with Art. 47 CFREU in conjunction with Art. 8 CFREU.

Final Remarks

These two posts are a first attempt to map copyright and data protection concerns surrounding ERT. It is clear that ERT poses considerable challenges to universities, teachers, and students, stressing a system which was already under pressure in many countries even before the COVID-19 crisis. Remote teaching is likely to remain the reality for some time, and it might permanently alter the way we approach academia and formal education. Several universities have already announced that teaching will continue online for the next semester. Therefore, it is essential to continue investigating the social and legal impacts of this swift but radical shift towards online teaching. To untangle the issues of content and data control, and – above all – the nature of our ERT infrastructure(s), we, the academic community, must carry out a thorough inquiry during this hectic time.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.