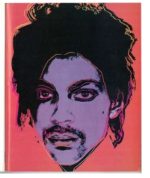

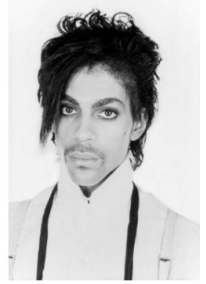

In March 2022 the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to review the Second Circuit’s ruling that Andy Warhol’s series of colorful prints and drawings of Prince were not transformative fair uses of Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph (for a previous comment on this case, see here). Vanity Fair magazine had commissioned Warhol’s artwork in 1984 to accompany an article about the singer’s rise to fame based on Goldsmith’s photograph under a one-time-use “artist reference” license between Vanity Fair and Goldsmith’s agent.

Many copyright professionals had hoped that the Court’s Goldsmith decision would articulate a workable standard for distinguishing transformative fair uses from infringing derivative works. Those hopes were largely dashed when the Court issued its decision in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith. The Court affirmed the Second Circuit only on the narrow issue of whether the Warhol Foundation (which controlled the rights to Andy Warhol’s works) had made a transformative use of Goldsmith’s photograph when it granted a license to Conde Nast in 2016 to use a Warhol print of Prince on the cover of a special issue magazine commemorating the life of this great performer after his untimely death in 2016.

Because both Goldsmith and the Foundation had licensed magazines to use their pictorial representations of Prince, the Court concluded the two works had the same purpose in this context and competed in the same market for magazine license revenues. Hence, the Foundation’s use was non-transformative. And because the Foundation had not appealed from the Second Circuit’s holdings on the other fair use factors, the Court concluded that an affirmance was warranted.

In the lower courts, the Foundation and Goldsmith had been fighting a different battle. The Foundation asserted that Warhol’s uses of Goldsmith’s photograph in 1984 were transformative fair uses while Goldsmith claimed that at the time of creation, Warhol’s works based on her photograph were infringing derivatives.

The Supreme Court expressly sidestepped the dispute over the 1984 creation of Warhol’s Prince series because in her respondent’s brief to the Court, Goldsmith abandoned her wider infringement claims. The brief focused instead on the unfairness of the Foundation’s receipt of $10,000 for the 2016 license granted to Conde Nast to use a Warhol work for a special issue.

Before discussing the Court’s latest fair use ruling, it is worth revisiting the positive valence of transformation in fair use cases since the Court’s 1994 decision in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. It held that 2 Live Crew’s rap parody version of a popular Ray Orbison song favored Campbell’s fair use defense because it had a “transformative” purpose. The Court defined this term as a use that “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message,” as Campbell’s parody certainly did. The song’s transformative purpose also affected the Court’s consideration of the market effects factor because transformative uses are much less likely to supplant demand for the original than non-transformative uses. No one, for instance, would purchase 2 Live Crew’s rap song if they wanted to listen to Roy Orbison’s rendition.

For nearly three decades, courts have given broad interpretations to the Campbell decision and its conception of transformative purposes as supporting fair use defenses. One such decision was the trial court’s ruling in Goldsmith that Warhol had made fair use of Goldsmith’s photograph because Warhol’s works conveyed a very different message and meaning than her photograph. Because of this, it concluded that Warhol’s works did not meaningfully compete with Goldsmith’s markets for her photograph. The Second Circuit’s reversal, among other things, rejected the “new meaning or message” as a meaningful criterion for judging transformative purposes.

The Court’s Goldsmith decision clarified that whether a second work has a “new meaning or message” may be relevant to whether a second comer’s use of a first work is fair, but on its own, it does not suffice. After all, many derivative works (say, a movie made from a novel) will add something new and convey some new meanings or messages. However, such uses must be licensed or be held unfair. Like the Second Circuit, the Court expressed concern that the Foundation’s interpretation of transformative purposes would unduly narrow an earlier author’s derivative work rights.

The Court in Goldsmith observed that when a second author’s work drawing upon a first author’s work has the same or a very similar purpose as the first work, harm to the first author’s markets is more likely. When a second author’s work has a different purpose than the first work, however, the second work’s use of the first work may be more justifiable. This is especially true when the second work comments on or criticizes the first work, as in Campbell, when 2 Live Crew parodied the Orbison song. Although Goldsmith did not hold that commentary or criticism is the sole justification for making use of parts of a first author’s works (Google’s uses of parts of the Java API, for instance, was justified for other reasons in the Oracle case), it is highly relevant, as is the degree to which the second use is commercial or noncommercial.

The most novel element of the Goldsmith decision was its insistence that each time a second comer uses parts of a first author’s work, the later use(s) must separately pass a fair use test. It is possible, for instance, that Warhol’s initial creation of the Prince series based on Goldsmith’s photograph might have been fair use (or were otherwise lawful, as Goldsmith’s abandonment of her larger infringement claim suggests). Yet this would not mean that these works were thereafter unencumbered by Goldsmith’s copyright. (The Court took no position on the legality of the works at the time of creation.)

The degree of this encumbrance may be quite narrow. Justice Gorsuch’s concurring opinion, which Justice Jackson joined, suggested that the Foundation’s commercial licensing of Warhol’s prints of Prince for a book commenting on twentieth-century art might be a fair use because it would have a different purpose than Goldsmith’s photograph; moreover, this market would not be one in which Goldsmith’s photograph competes. Justice Gorsuch further suggested that displays of Warhol’s works on nonprofit museum walls might similarly qualify as fair uses. Each challenged use, he said, must be assessed on its own terms.

Courts and commentators now face the difficult task of readjusting their understandings of fair use defenses after the Goldsmith decision. Some are likely to give it a very broad interpretation, while others may argue that it is a much narrower ruling than some dicta in Justice Sotomayor’s opinion might suggest.

What we know for sure is that a “new meaning or message” in secondary works is only relevant to, but not dispositive of, transformative purposes. In the aftermath of Goldsmith, courts will be asking putative fair users to justify each use of pre-existing works. The larger question of how courts should distinguish infringing derivatives from transformative fair uses must await another case to be definitively answered.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.

Kluwer IP Law

The 2022 Future Ready Lawyer survey showed that 79% of lawyers think that the importance of legal technology will increase for next year. With Kluwer IP Law you can navigate the increasingly global practice of IP law with specialized, local and cross-border information and tools from every preferred location. Are you, as an IP professional, ready for the future?

Learn how Kluwer IP Law can support you.